Related Articles

- 13 Apr 20

Although it has been fraught with debate, and even disdain on occasion, the use of airbrushing of photos emanating from the marketing world of skin care and beauty tells us one thing: our society has a desire for evenness in skin appearance.

- 05 May 20

Acne (or acne vulgaris) is one of the most common skin conditions, affecting 64% of people in their 20s and 43% of people in their 30s. It affects the pilosebaceous units of the skin, which is essentially the oil gland and hair follicle. It usually affects the largest, hormone-responsive sebaceous glands such as those on the face, chest, neck and back.

- 13 Apr 20

Itchy skin, dryness, redness, and cracking—uncomfortable signs of an eczema flare-up that can range from mild to having a significant impact on quality of life. Corticosteroid creams can do a fine job of targeting symptoms and inflammation associated with eczema, although below are some suggestions to get to the root cause and prevent future flare-ups.

- 17 Dec 19

Collagen peptides have seemingly appeared out of nowhere. They are being advertised on social media, can be found on the covers of magazines… even my hairdresser has been talking about how she adds collagen peptides to her smoothie! But what are collagen peptides? Why is everyone adding this powder to their coffee, smoothies, or breakfast oatmeal bowl? And the real question is: Should you be adding collagen peptides to your diet as well?

- 15 Jun 23

Cellulite represents a localized skin concern typically found over the posterolateral thighs, buttocks, and abdomen. The skin surface over such areas is often found to exhibit dimpling or an “orange-peel” appearance

- 13 Apr 17

- 13 Oct 15

- 08 Jun 15

Niacin is one form of vitamin B3. Niacinamide and inositol hexanicotinate are the other two forms of B3 that exist; these forms are generally used to treat different conditions within the body. B vitamins ultimately help the body utilize fats and proteins; they also help convert food into fuel which is then used to produce energy.

Niacin is one form of vitamin B3. Niacinamide and inositol hexanicotinate are the other two forms of B3 that exist; these forms are generally used to treat different conditions within the body. B vitamins ultimately help the body utilize fats and proteins; they also help convert food into fuel which is then used to produce energy. - 13 Feb 16

Noticing blood while brushing or flossing can be alarming and shouldn’t be ignored! The importance of oral health is a concept introduced to most Canadians at a very young age, and with good reason. The Ontario Dental Hygienist’s Association reports that the link between oral infections and other diseases in the body is becoming well-documented and accepted within the health-care community. Periodontal disease is one of the most common human diseases

Noticing blood while brushing or flossing can be alarming and shouldn’t be ignored! The importance of oral health is a concept introduced to most Canadians at a very young age, and with good reason. The Ontario Dental Hygienist’s Association reports that the link between oral infections and other diseases in the body is becoming well-documented and accepted within the health-care community. Periodontal disease is one of the most common human diseases - 02 Sep 15

- 03 Nov 16

- 13 Apr 15

Periodontitis is the result of gingivitis progressing to a more serious stage. It is characterized by swollen, reddish, and bleeding gums, as well as bad breath. Severe periodontitis affects 10–15% of adults, while moderate periodontitis affects 40–60% of adults. Despite its high prevalence, it is largely unrepresented as a chronic inflammatory disease.

Periodontitis is the result of gingivitis progressing to a more serious stage. It is characterized by swollen, reddish, and bleeding gums, as well as bad breath. Severe periodontitis affects 10–15% of adults, while moderate periodontitis affects 40–60% of adults. Despite its high prevalence, it is largely unrepresented as a chronic inflammatory disease. - 13 Feb 17

- 17 Jul 16

- 09 Jul 15

And so it begins. You find few strands of hair on your pillow and more than the usual amount on your hair brush. As you are cleaning your house, you begin to notice hair on the floor, in the shower, on your clothes, and then it dawns on you that you are not only leaving behind a trail of hair in every area of the house, but a hairless patch possibly somewhere on your scalp.

And so it begins. You find few strands of hair on your pillow and more than the usual amount on your hair brush. As you are cleaning your house, you begin to notice hair on the floor, in the shower, on your clothes, and then it dawns on you that you are not only leaving behind a trail of hair in every area of the house, but a hairless patch possibly somewhere on your scalp. - 08 Nov 18

Cleansers, toners, AM moisturizers, PM moisturizers, sunscreens, serums, gels, and ointments… With infomercials showcasing amazing before-and-after effects, and the daunting number of products lining cosmetics store shelves, acne can be challenging to manage. Is a regimen using a multitude of products necessary? What ingredients should be looked for if they are needed?

- 09 Jul 15

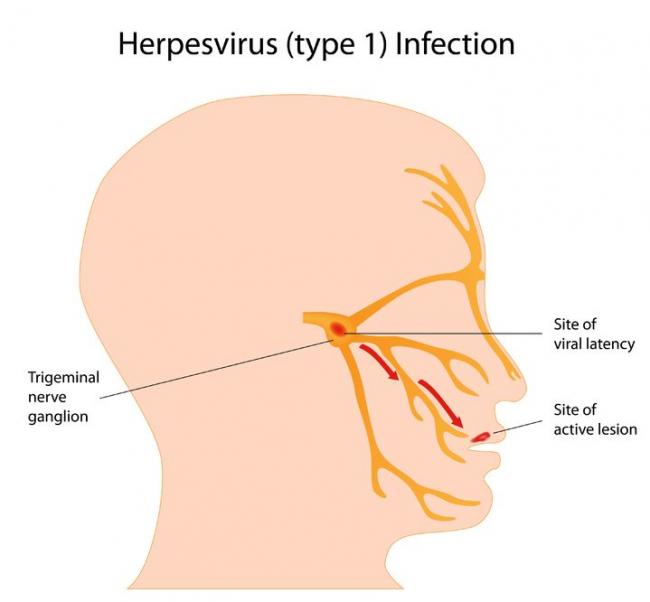

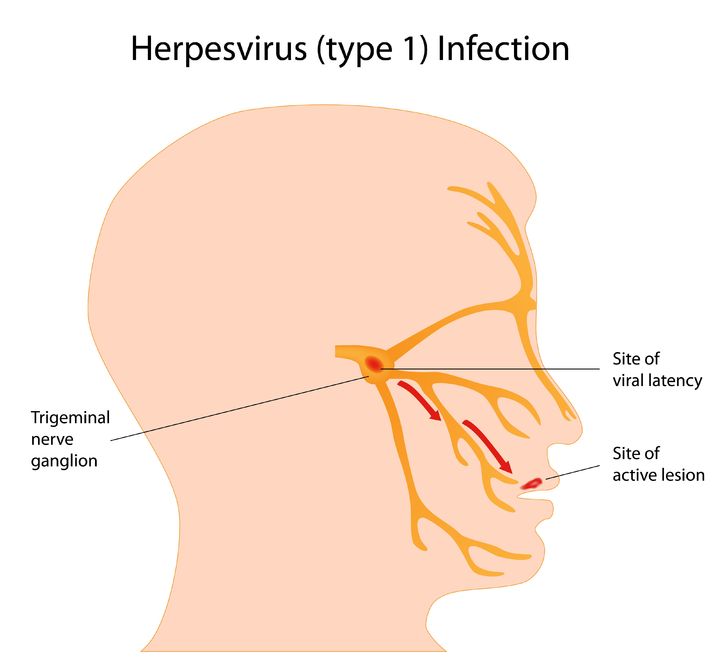

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a viral infection of the skin and mucous membranes. Lesions can occur in many different areas, especially in or around the mouth, lips, genitals, and eyes. There are two types of HSV that exist: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 is responsible for the development of your typical “cold sore”; it therefore has a predisposition for the mouth and lips,

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a viral infection of the skin and mucous membranes. Lesions can occur in many different areas, especially in or around the mouth, lips, genitals, and eyes. There are two types of HSV that exist: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 is responsible for the development of your typical “cold sore”; it therefore has a predisposition for the mouth and lips, - 13 Oct 15

- 09 Nov 15

Who we are and how we feel is often expressed through our hair. Regardless of if hair is curly, straight, twisted, corn-rowed or locked; it is a universal sign of beauty, sensuality, fertility and attractiveness. Moreover, hair helps us to communicate our state of health. It also serves the function of protecting our heads and skin, adding not only a layer of insulation, but also more dimension to our personalities.

Who we are and how we feel is often expressed through our hair. Regardless of if hair is curly, straight, twisted, corn-rowed or locked; it is a universal sign of beauty, sensuality, fertility and attractiveness. Moreover, hair helps us to communicate our state of health. It also serves the function of protecting our heads and skin, adding not only a layer of insulation, but also more dimension to our personalities. - 29 Jan 21

After iron, zinc is the most abundant element in the human body, with approximately 2 to 4 g distributed among the muscles (60%), bones (20%), liver, and skin. Given its abundance, concerns about zinc deficiency is often overlooked; however, as discussed in this article, certain populations and individuals may benefit from supplementation.

Newsletter

Most Popular

- 09 Nov 15

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13