Related Articles

- 12 Feb 20

Endometriosis is one of the most common chronic gynecological conditions in women of reproductive age. Not only is it associated with severe, debilitating pain, but it can also have significant implications for a woman’s fertility.[1]

- 09 Jan 20

Premenstrual symptoms affect up to 80% of women. For many, these symptoms are bothersome but do not necessarily impact their daily functioning. Premenstrual syndrome (PMS), however, affects up to 20% of women. This diagnosis is defined by a woman’s experience of at least one physical and one psychiatric symptom each month in the second half of her cycle (7–14 days before her period), that alleviate with or shortly after the onset of menses.

- 05 May 20

Acne (or acne vulgaris) is one of the most common skin conditions, affecting 64% of people in their 20s and 43% of people in their 30s. It affects the pilosebaceous units of the skin, which is essentially the oil gland and hair follicle. It usually affects the largest, hormone-responsive sebaceous glands such as those on the face, chest, neck and back.

- 08 Jul 20

With pregnancy come major changes in circulation. It’s no wonder: With an increase in body weight from the fetus and surrounding fluid, extra pressure is added onto organs and other structures like the weaker-walled veins. The body’s blood volume also increases and these changes can result in swelling, varicose veins, and hemorrhoids.

- 08 Jul 20

Hormones are essential signaling molecules in the body, but can create extreme pain and discomfort for women if they are out of balance. Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) has been the brunt of many jokes over many decades. However, the truth of this syndrome can be devastating for the sufferer, her relationships and her career.

- 08 Jul 20

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common endocrine disorders. PCOS affects one in every five women of the reproductive age.

- 27 Apr 22

One of the key tenants of naturopathic medicine is education. In fact, one of the guiding principles of Naturopathic Medicine is Doctor as Teacher . This principle highlights the empowering nature of naturopathic medicine. A naturopathic doctor simply provides the tools, education, and resources for each patient to work on their own healing.

- 23 Dec 16

Dies ist Teil 2 unseres zweiteiligen Artikels zu Möglichkeiten der Geburtenkontrolle neben der „Pille“.

Teil 1 behandelte die Hormon- und Kupferspiralen. Teil 2 deckt den Ring, das Pflaster, das Diaphragma, die Kondome und die Rhythmusmethode ab. - 02 Sep 15

- 11 Aug 15

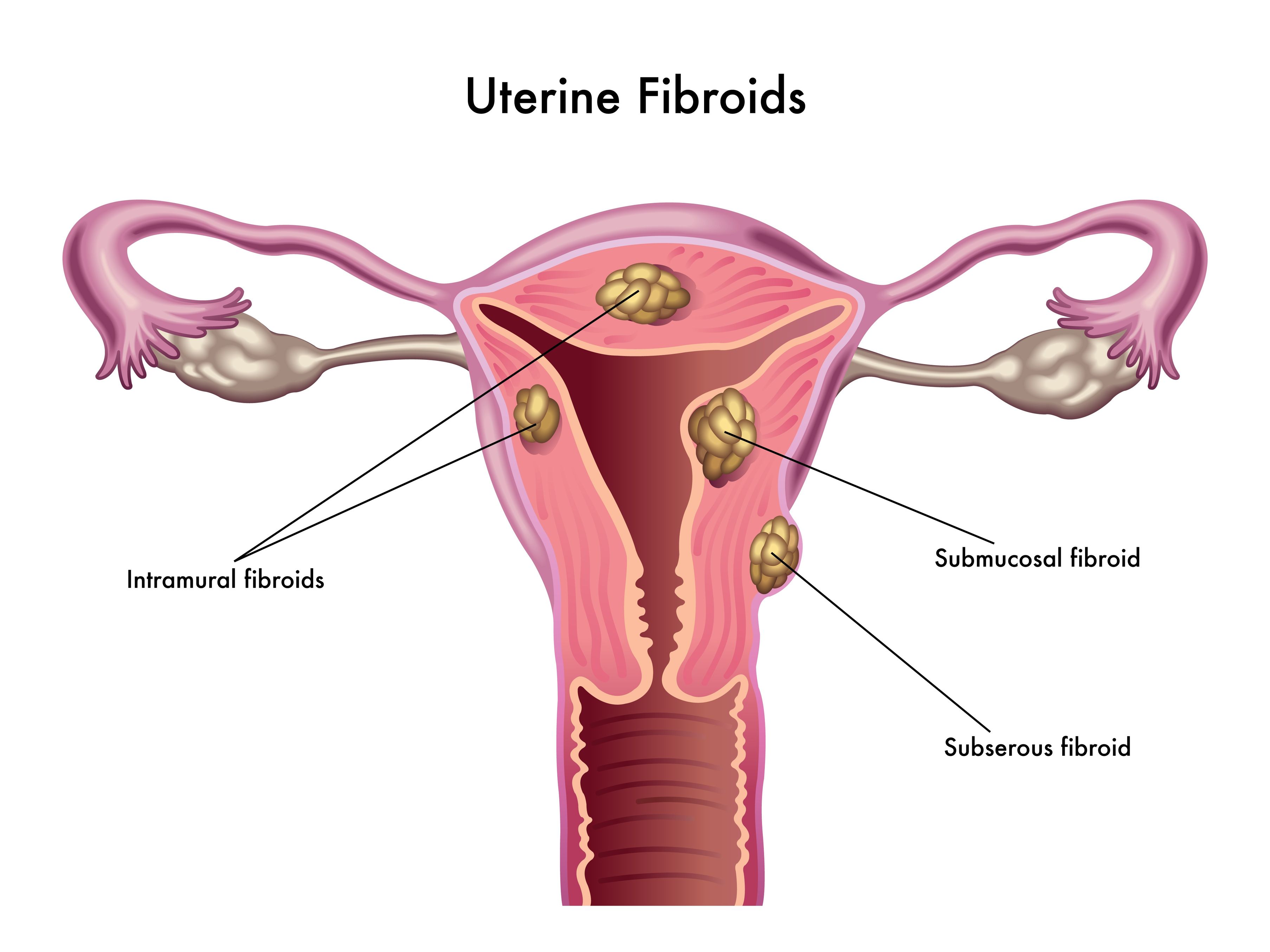

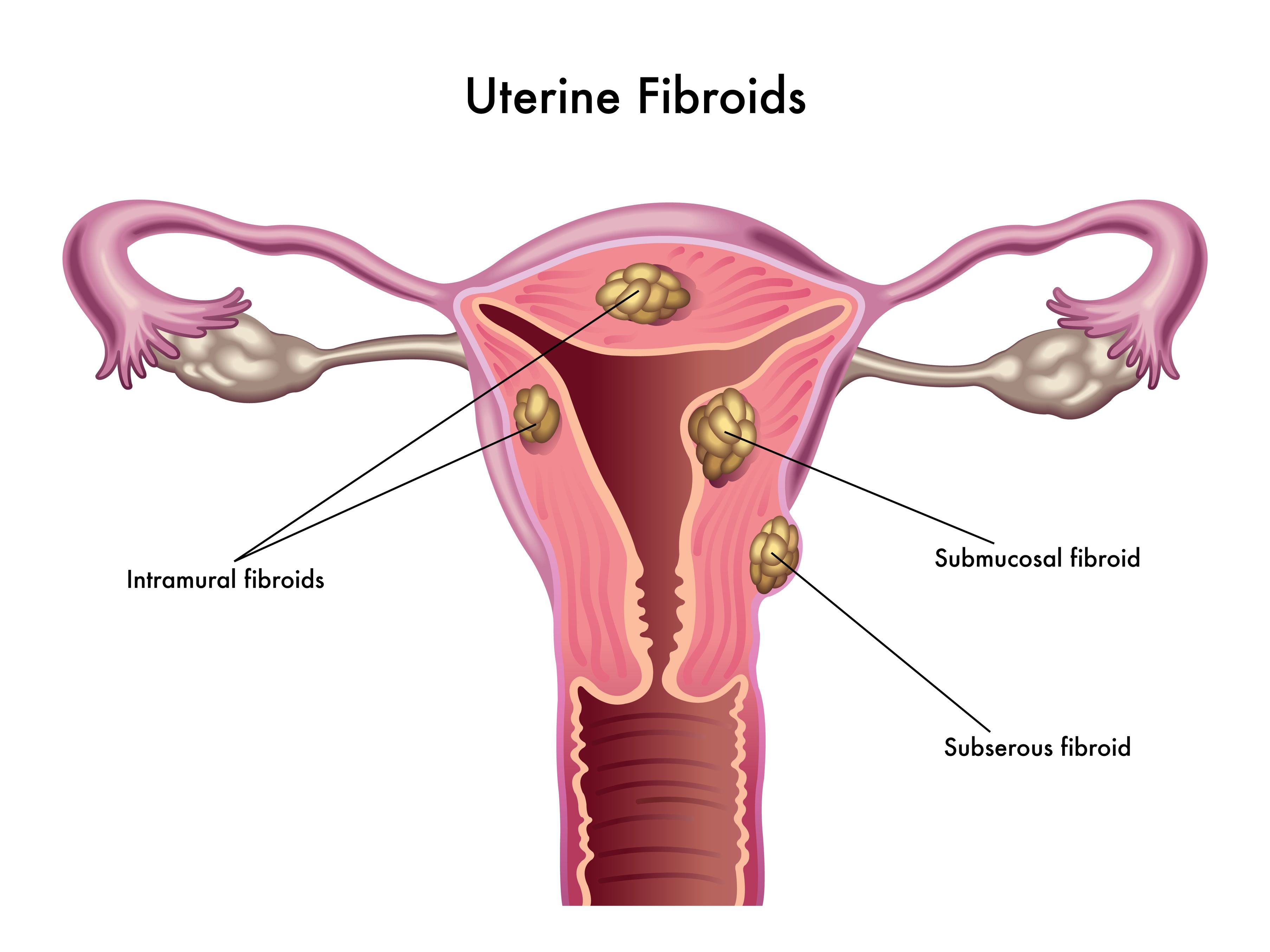

Uterine fibroids (also known as leiomyomas) are solid pelvic tumors composed of connective tissue and muscle [1]. Leiomyomas vary in terms of size, shape, and location; if one leiomyoma is discovered chances are multiple exist. Leiomyomas are either submucosal (under the endometrium), intramural (within the uterine wall), or subserosal (in the outer wall of the uterus).

Uterine fibroids (also known as leiomyomas) are solid pelvic tumors composed of connective tissue and muscle [1]. Leiomyomas vary in terms of size, shape, and location; if one leiomyoma is discovered chances are multiple exist. Leiomyomas are either submucosal (under the endometrium), intramural (within the uterine wall), or subserosal (in the outer wall of the uterus). - 06 Sep 16

- 08 Jan 15

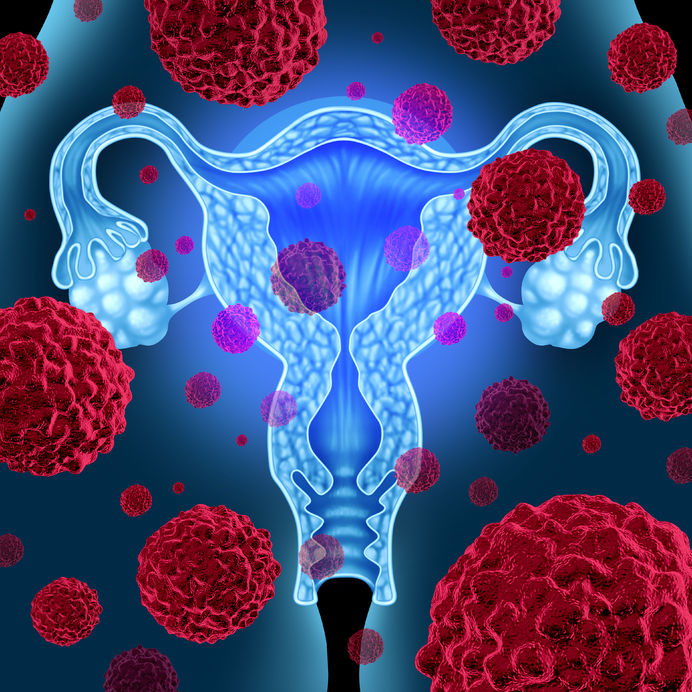

Cervical dysplasia refers to abnormal cells found on the surface of the cervix, that are considered to be premalignant and can progress to cancer.[1] Cervical dysplasia is primarily caused by a sexually transmitted infection with different strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV). However, different strains can be involved in both benign and malignant lesions; therefore, the progression of the disease appears to depend on individual factors. Studies suggest that HPV exposure is the initiating event that can lead to the development of cervical dysplasia, often termed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

Cervical dysplasia refers to abnormal cells found on the surface of the cervix, that are considered to be premalignant and can progress to cancer.[1] Cervical dysplasia is primarily caused by a sexually transmitted infection with different strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV). However, different strains can be involved in both benign and malignant lesions; therefore, the progression of the disease appears to depend on individual factors. Studies suggest that HPV exposure is the initiating event that can lead to the development of cervical dysplasia, often termed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). - 07 May 15

Fibrocystic breasts are characterized as ‘lumps’ or ‘cysts’ found within the breast. Fibrocystic breasts arise from estrogen predominance and progesterone deficiency resulting in hyper-proliferation of connective tissue. This condition can be either asymptomatic or present with breast nodularity, swelling, and pain.

Fibrocystic breasts are characterized as ‘lumps’ or ‘cysts’ found within the breast. Fibrocystic breasts arise from estrogen predominance and progesterone deficiency resulting in hyper-proliferation of connective tissue. This condition can be either asymptomatic or present with breast nodularity, swelling, and pain. - 17 Aug 16

- 06 Oct 16

- 13 Apr 17

- 06 Oct 14

- 09 Nov 17

Most women are very familiar with premenstrual syndrome (PMS), though how each individual woman experiences PMS can vary completely. Rapid fluctuations in sex hormones can lead to changes in energy, mood, and/or physical symptoms throughout her cycle, most predominantly during the last week of the luteal phase.

Most women are very familiar with premenstrual syndrome (PMS), though how each individual woman experiences PMS can vary completely. Rapid fluctuations in sex hormones can lead to changes in energy, mood, and/or physical symptoms throughout her cycle, most predominantly during the last week of the luteal phase. - 16 Jan 16

- 10 Mar 18

Prenatal genetic testing is used to determine if a fetus has, or is at risk of developing, a genetic disorder. These disorders are caused by changes, often deletions or duplications, in fetal DNA and chromosomes. Two main types of testing often performed are screening and diagnosis. Screening tests typically look for aneuploidy—an abnormal number of chromosomes

Newsletter

Most Popular

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13