Related Articles

- 13 Apr 20

Have you met the people that tell you, quite proudly, they never, ever, ever get sick? Do you find yourself feeling just a wee bit jealous? Well, feel jealous no more! Exercising our immune system with a good fever may feel yucky, but it is great for all kinds of reasons.

- 09 Mar 20

The viruses that cause colds and the flu can be spread easily by coughing and sneezing. While there is no way to guarantee you won’t get sick this winter, there are things you can do to reduce the severity of your sickness.

- 05 May 20

Climate change is possibly the most important issue of the twenty-first century. The long-term changes in the temperature of our planet will continue to impact not only our environments, but also our food and our health. These small changes are not noticeable on a daily basis, but as the years go by, the steady change over the years cannot be ignored.

- 11 Aug 15

Lower urinary tract infections (referred to as UTIs in this article) account for millions of doctor visits per year with the urinary tract being the second-most common site for infection. The term urinary tract infection refers to the presence of a certain number of bacteria in the urine, usually more than 100 000/mL. UTIs can occur in both men and women, however, they are about fifty times more common in women than men.

Lower urinary tract infections (referred to as UTIs in this article) account for millions of doctor visits per year with the urinary tract being the second-most common site for infection. The term urinary tract infection refers to the presence of a certain number of bacteria in the urine, usually more than 100 000/mL. UTIs can occur in both men and women, however, they are about fifty times more common in women than men. - 13 Feb 16

Noticing blood while brushing or flossing can be alarming and shouldn’t be ignored! The importance of oral health is a concept introduced to most Canadians at a very young age, and with good reason. The Ontario Dental Hygienist’s Association reports that the link between oral infections and other diseases in the body is becoming well-documented and accepted within the health-care community. Periodontal disease is one of the most common human diseases

Noticing blood while brushing or flossing can be alarming and shouldn’t be ignored! The importance of oral health is a concept introduced to most Canadians at a very young age, and with good reason. The Ontario Dental Hygienist’s Association reports that the link between oral infections and other diseases in the body is becoming well-documented and accepted within the health-care community. Periodontal disease is one of the most common human diseases - 02 Sep 15

- 03 Feb 15

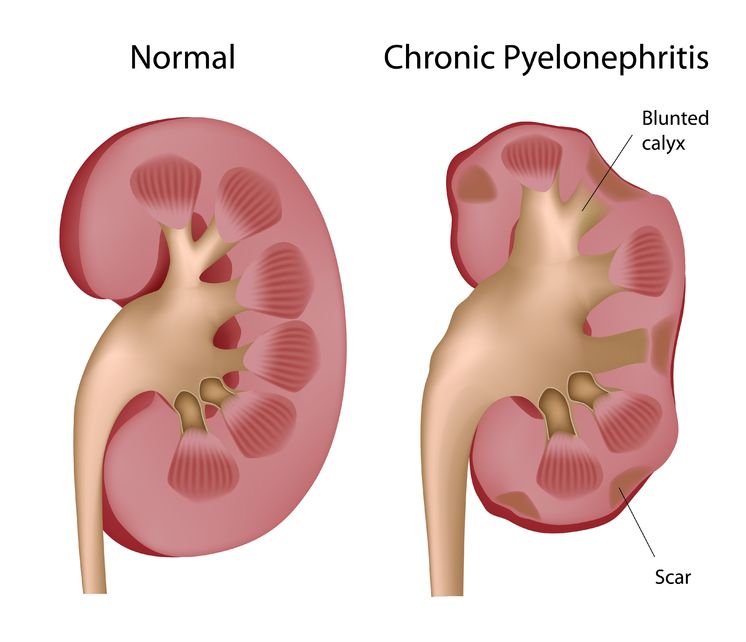

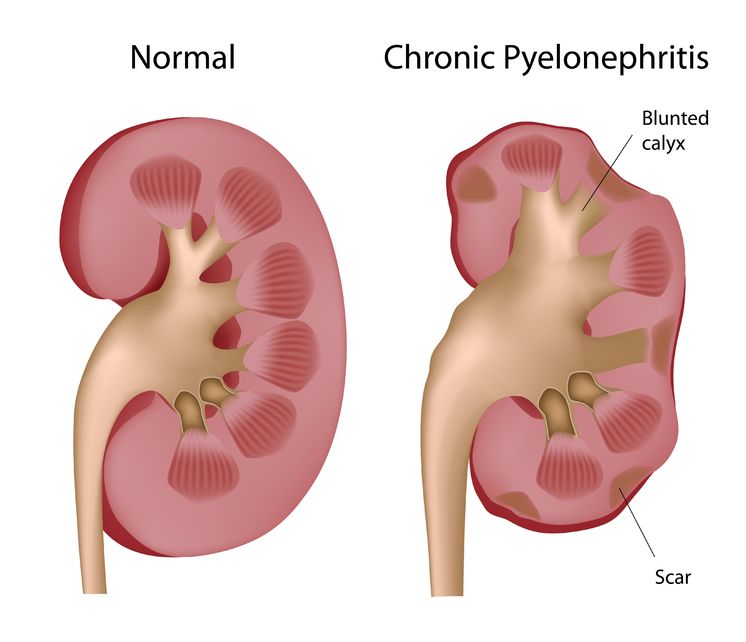

Pyelonephritis is the result of a progressive urinary tract infection, when a lower urinary infection travels upward into the upper urinary system. The lower urinary infections originate in the bladder and urethra, while the upper urinary infections involve the ureters and the kidneys. The kidneys filter the blood, so pyelonephritis can be potentially dangerous because an infection could then spread into the bloodstream.

Pyelonephritis is the result of a progressive urinary tract infection, when a lower urinary infection travels upward into the upper urinary system. The lower urinary infections originate in the bladder and urethra, while the upper urinary infections involve the ureters and the kidneys. The kidneys filter the blood, so pyelonephritis can be potentially dangerous because an infection could then spread into the bloodstream. - 13 Apr 15

The “stomach flu” or a “stomach bug” are the common names for what is officially known in medicine as gastroenteritis. Gastroenteritis essentially means “inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract”; it usually involves the stomach and the intestines. It causes a set of highly unpleasant symptoms: usually a combination of diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and abdominal cramping.

The “stomach flu” or a “stomach bug” are the common names for what is officially known in medicine as gastroenteritis. Gastroenteritis essentially means “inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract”; it usually involves the stomach and the intestines. It causes a set of highly unpleasant symptoms: usually a combination of diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and abdominal cramping. - 09 Mar 15

Origanum vulgare (the scientific name of oregano) has been studied in depth due to a number of interesting and exciting potential clinical uses. There is also an ongoing interest in a number of industries to replace synthetic chemicals with natural products that have similar properties. Many bioactive compounds can be found in aromatic plants, and there are a number of different ways they can be extracted.

Origanum vulgare (the scientific name of oregano) has been studied in depth due to a number of interesting and exciting potential clinical uses. There is also an ongoing interest in a number of industries to replace synthetic chemicals with natural products that have similar properties. Many bioactive compounds can be found in aromatic plants, and there are a number of different ways they can be extracted. - 08 Jan 15

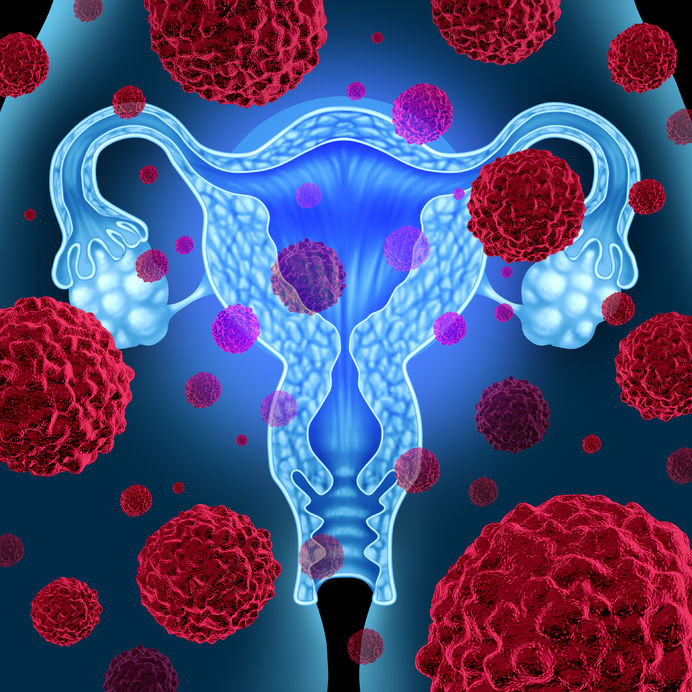

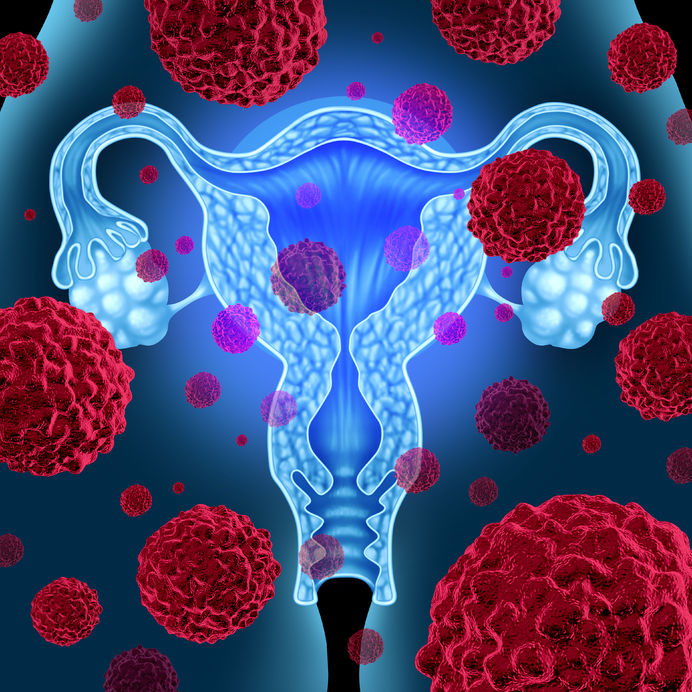

Cervical dysplasia refers to abnormal cells found on the surface of the cervix, that are considered to be premalignant and can progress to cancer.[1] Cervical dysplasia is primarily caused by a sexually transmitted infection with different strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV). However, different strains can be involved in both benign and malignant lesions; therefore, the progression of the disease appears to depend on individual factors. Studies suggest that HPV exposure is the initiating event that can lead to the development of cervical dysplasia, often termed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

Cervical dysplasia refers to abnormal cells found on the surface of the cervix, that are considered to be premalignant and can progress to cancer.[1] Cervical dysplasia is primarily caused by a sexually transmitted infection with different strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV). However, different strains can be involved in both benign and malignant lesions; therefore, the progression of the disease appears to depend on individual factors. Studies suggest that HPV exposure is the initiating event that can lead to the development of cervical dysplasia, often termed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). - 16 Jan 16

An old adage taunts us with the fact that for years medicine has struggled to beat what we call the ‘common cold’ with mild success at best, but boy have we ever tried. Walk into a drugstore any time of the year and you will find shelves stocked with nostalgic cherry tasting syrups, pills to relieve symptoms and keep you awake, others help you sleep,

An old adage taunts us with the fact that for years medicine has struggled to beat what we call the ‘common cold’ with mild success at best, but boy have we ever tried. Walk into a drugstore any time of the year and you will find shelves stocked with nostalgic cherry tasting syrups, pills to relieve symptoms and keep you awake, others help you sleep, - 04 Oct 17

Interstitial cystitis is a multifactorial condition and no single pathological process is present universally in patients with IC. It is thus important to determine the root causes of the individual’s symptoms, which commonly include bladder-wall dysfunction and permeability, urine acidity, and infection.

Interstitial cystitis is a multifactorial condition and no single pathological process is present universally in patients with IC. It is thus important to determine the root causes of the individual’s symptoms, which commonly include bladder-wall dysfunction and permeability, urine acidity, and infection. - 06 Oct 16

- 09 Jul 15

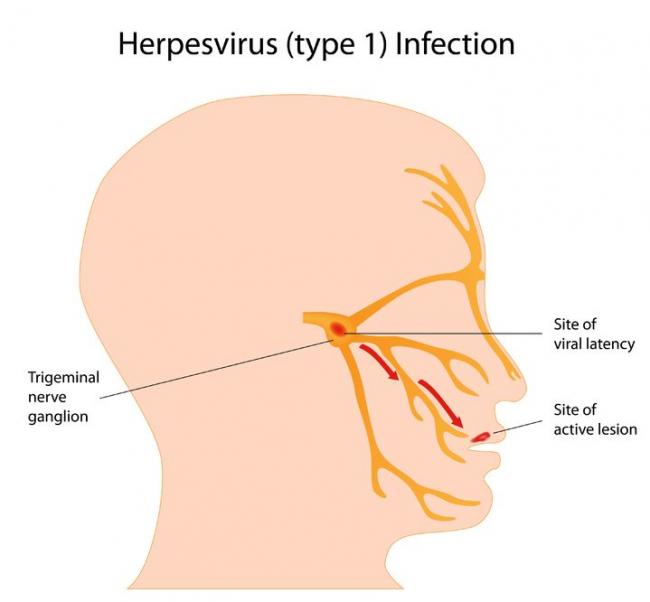

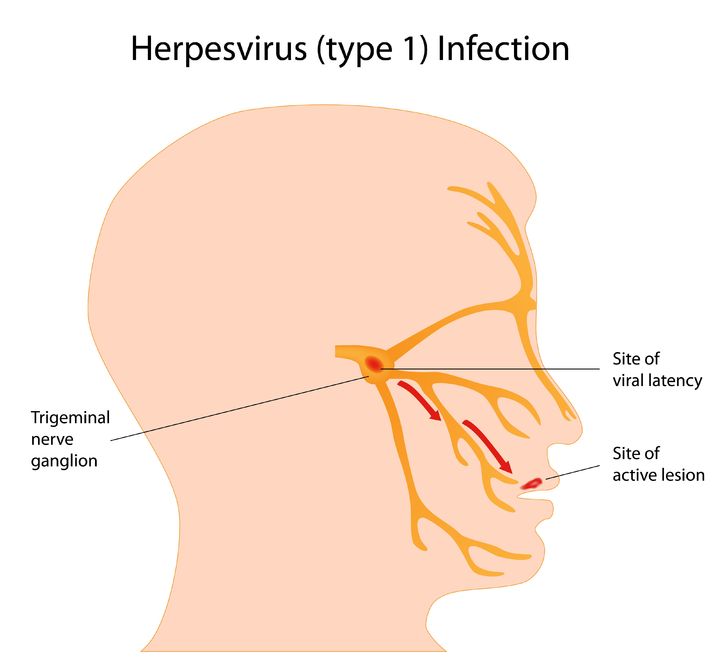

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a viral infection of the skin and mucous membranes. Lesions can occur in many different areas, especially in or around the mouth, lips, genitals, and eyes. There are two types of HSV that exist: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 is responsible for the development of your typical “cold sore”; it therefore has a predisposition for the mouth and lips,

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a viral infection of the skin and mucous membranes. Lesions can occur in many different areas, especially in or around the mouth, lips, genitals, and eyes. There are two types of HSV that exist: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 is responsible for the development of your typical “cold sore”; it therefore has a predisposition for the mouth and lips, - 06 Aug 14

Liver diseases include a number of different health conditions; in conventional medicine, they are bundled under the umbrella term “hepatology”, which typically includes the health conditions related to the liver, the gallbladder, and the pancreas. Over the last several years, there has been an increase in the use of complementary and alternative medicines, especially herbal therapies, among patients with liver disease.

- 18 Mar 19

Over 50% of women will suffer from a urinary tract infection (UTI) during their lifetime. One-third to one-half of these women will have a recurrent UTI within one year.

- 14 Jun 18

Shingles is often touted as an infection of the elderly. We see commercials on TV for the shingles vaccine, and everyone pictured is over the age of 60. Perhaps the pain of shingles can be much more debilitating at that age, but the reality is that anyone who has had chickenpox is susceptible to shingles—no matter how old you are.

- 06 Oct 14

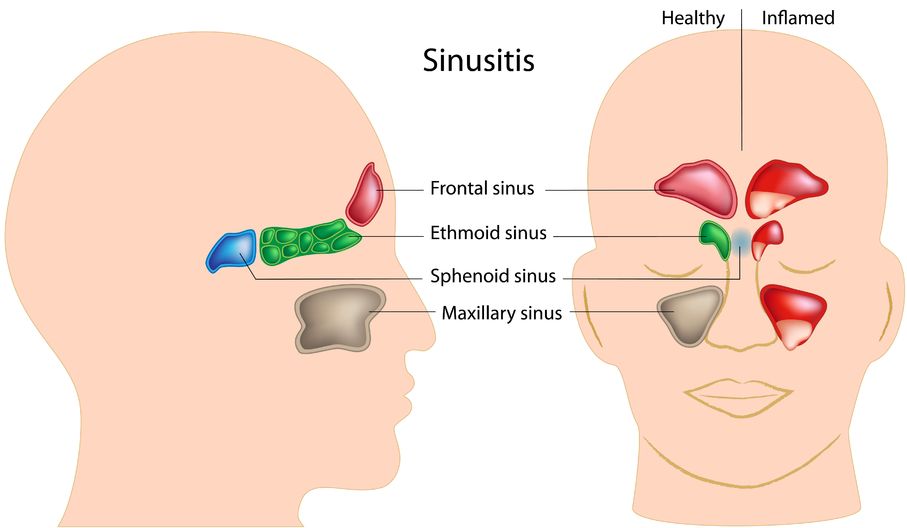

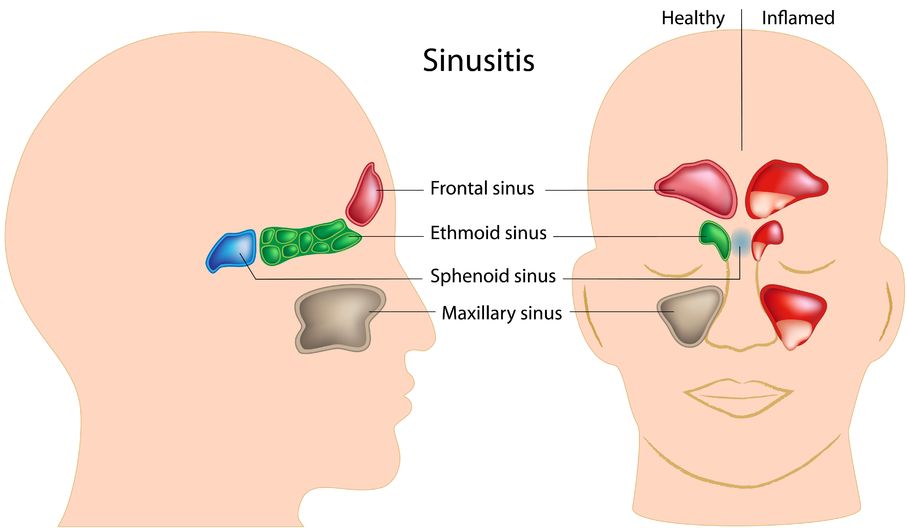

Sinusitis is the inflammation of the sinuses. The sinuses are actually a system of openings or cavities that are part of the skull. The largest one is the maxillary sinus, located near the cheekbones. It is often the one that most people complain about when they are experiencing facial pain. The other sinuses include the frontal sinuses, the ethmoid sinuses, and the sphenoid sinuses.

Sinusitis is the inflammation of the sinuses. The sinuses are actually a system of openings or cavities that are part of the skull. The largest one is the maxillary sinus, located near the cheekbones. It is often the one that most people complain about when they are experiencing facial pain. The other sinuses include the frontal sinuses, the ethmoid sinuses, and the sphenoid sinuses. - 15 Jan 17

- 11 Mar 16

Vaginal yeast infections can be extremely uncomfortable and significantly impact the quality of a woman’s life. At least 75% of women will experience a yeast infection once in their lifetime, with 45% experiencing two or more episodes, and 5–8% experiencing frequently recurring infections over the course of their life.

Vaginal yeast infections can be extremely uncomfortable and significantly impact the quality of a woman’s life. At least 75% of women will experience a yeast infection once in their lifetime, with 45% experiencing two or more episodes, and 5–8% experiencing frequently recurring infections over the course of their life.

Newsletter

Most Popular

- 09 Jul 15

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13