Related Articles

- 17 May 18

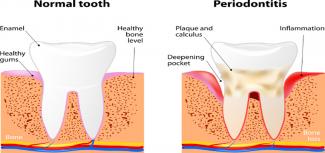

Sure, dental cleaning is great for our oral health, but did you know that it can also improve the wellness of your whole body? Daily toothbrushing and flossing is crucial to maintain the health of our gums and teeth; however, this might actually be more important in pregnant women and those looking to conceive.

- 23 Dec 16

- 03 Mar 14

The number of couples experiencing infertility and/or resorting to assisted reproductive technology (ART) is on the rise. A study released in 2012 found that among Canadian couples (women aged 18–44 years), the prevalence of infertility ranged from 11 to 15%, and this was an increase compared to previous statistics. 05 Aug 14

The number of couples experiencing infertility and/or resorting to assisted reproductive technology (ART) is on the rise. A study released in 2012 found that among Canadian couples (women aged 18–44 years), the prevalence of infertility ranged from 11 to 15%, and this was an increase compared to previous statistics. 05 Aug 14 The term “dysmenorrhea” is commonly used to describe painful menstruation. Considered one of the most common conditions in women’s health, its effective treatment relies on determining and addressing the root cause. When the pain is due to a specific pelvic or systemic condition, it is referred to as “secondary dysmenorrhea”; in the absence of disease or physical abnormalities, menstrual pain is referred to as “primary dysmenorrhea”.02 Jun 17

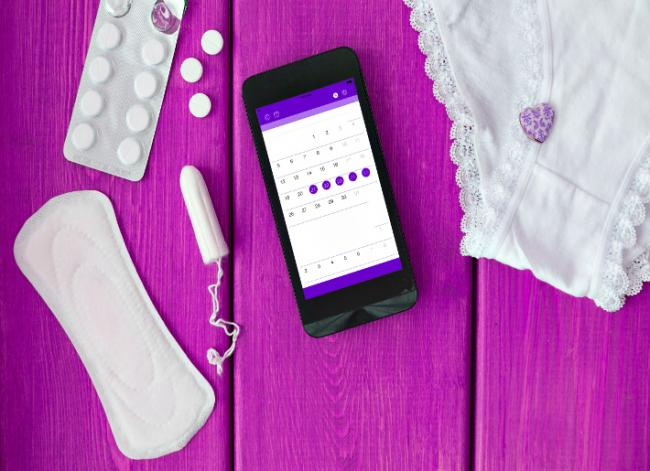

The term “dysmenorrhea” is commonly used to describe painful menstruation. Considered one of the most common conditions in women’s health, its effective treatment relies on determining and addressing the root cause. When the pain is due to a specific pelvic or systemic condition, it is referred to as “secondary dysmenorrhea”; in the absence of disease or physical abnormalities, menstrual pain is referred to as “primary dysmenorrhea”.02 Jun 17 Understanding your menstrual cycle involves more than just estimating your next period. Knowing your body and tracking your menstrual cycles can provide insight into your hormonal and reproductive health. You might be experiencing symptoms that we usually label as “normal,” when we should be calling them “common.”15 Jan 1711 Mar 16

Understanding your menstrual cycle involves more than just estimating your next period. Knowing your body and tracking your menstrual cycles can provide insight into your hormonal and reproductive health. You might be experiencing symptoms that we usually label as “normal,” when we should be calling them “common.”15 Jan 1711 Mar 16 Vaginal yeast infections can be extremely uncomfortable and significantly impact the quality of a woman’s life. At least 75% of women will experience a yeast infection once in their lifetime, with 45% experiencing two or more episodes, and 5–8% experiencing frequently recurring infections over the course of their life.25 May 16

Vaginal yeast infections can be extremely uncomfortable and significantly impact the quality of a woman’s life. At least 75% of women will experience a yeast infection once in their lifetime, with 45% experiencing two or more episodes, and 5–8% experiencing frequently recurring infections over the course of their life.25 May 16 Whether by unmediated naturals means, induction, or caesarean section, the birth of a child can be an exciting, frightening, and overwhelming experience, and all this is just within in the first moments of life! While some birth experiences go on exactly as planned, others are not as routine, and fortunately procedures such as caesarean delivery (CD) are available to those who might otherwise suffer the negative consequences that can be associated with the birthing process.09 Nov 15

Whether by unmediated naturals means, induction, or caesarean section, the birth of a child can be an exciting, frightening, and overwhelming experience, and all this is just within in the first moments of life! While some birth experiences go on exactly as planned, others are not as routine, and fortunately procedures such as caesarean delivery (CD) are available to those who might otherwise suffer the negative consequences that can be associated with the birthing process.09 Nov 15 Who we are and how we feel is often expressed through our hair. Regardless of if hair is curly, straight, twisted, corn-rowed or locked; it is a universal sign of beauty, sensuality, fertility and attractiveness. Moreover, hair helps us to communicate our state of health. It also serves the function of protecting our heads and skin, adding not only a layer of insulation, but also more dimension to our personalities.11 Oct 18

Who we are and how we feel is often expressed through our hair. Regardless of if hair is curly, straight, twisted, corn-rowed or locked; it is a universal sign of beauty, sensuality, fertility and attractiveness. Moreover, hair helps us to communicate our state of health. It also serves the function of protecting our heads and skin, adding not only a layer of insulation, but also more dimension to our personalities.11 Oct 18Your period is late—really late. You’re not pregnant, and you’re not menopausal. You may have missed one cycle or several. Of course, it’s worrisome: Many women who have missed one or more periods often take several pregnancy tests just to be certain. But the causes of a missed period go well beyond the possibility of pregnancy.

15 Sep 1728 Apr 22Hypothyroidism is one of the most common endocrine disorders worldwide. Hypothyroidism and subclinical hypothyroidism have a prevalence rate of 4–5% and 4–15%, respectively. The prevalence is around three to seven times higher in women than men, and its incidences proportionally increase with age.

03 Mar 14 Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a condition consisting of ovulatory dysfunction and hyperandrogenism, defined as excess activity of testosterone and related androgen hormones. PCOS affects approximately 10% of women of reproductive age, and is a common cause of infertility. However, women with PCOS often suffer from more subtle disturbances in other hormone axes as well, such as thyroid and adrenal systems.

10 Apr 16

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a condition consisting of ovulatory dysfunction and hyperandrogenism, defined as excess activity of testosterone and related androgen hormones. PCOS affects approximately 10% of women of reproductive age, and is a common cause of infertility. However, women with PCOS often suffer from more subtle disturbances in other hormone axes as well, such as thyroid and adrenal systems.

10 Apr 16 Every woman—if she lives long enough—will experience menopause. For some, the transition is easy and can even be a relief from the troubles of a regular menstrual cycle. For others, the change is extremely challenging as they struggle to manage frequent “hot flashes,” weight gain, and severe depression. Many of the symptoms of menopause can be directly related to the decreased production of sex hormones— specifically estrogen and progesterone.11 Sep 1704 Oct 1703 Feb 15

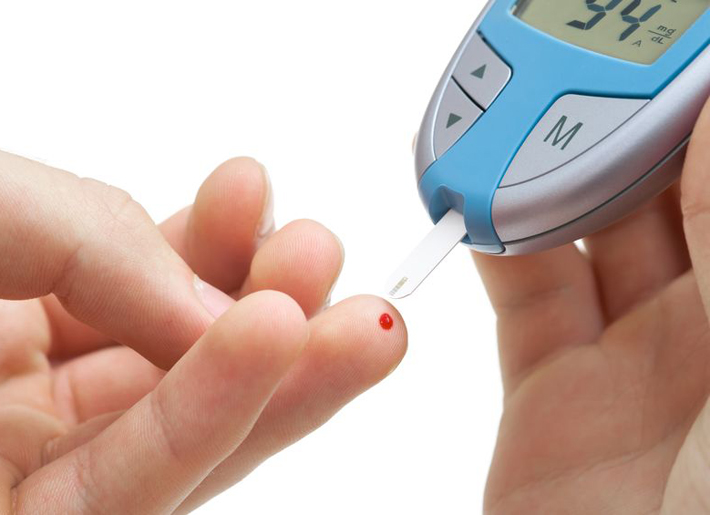

Every woman—if she lives long enough—will experience menopause. For some, the transition is easy and can even be a relief from the troubles of a regular menstrual cycle. For others, the change is extremely challenging as they struggle to manage frequent “hot flashes,” weight gain, and severe depression. Many of the symptoms of menopause can be directly related to the decreased production of sex hormones— specifically estrogen and progesterone.11 Sep 1704 Oct 1703 Feb 15 Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a pregnancy complication defined as impaired blood sugar regulation beginning in pregnancy, and is no longer present after delivery. Although prevalence varies, a recent study by the CDC reports that as many as 9.2% of pregnancies are affected by gestational diabetes.18 Oct 19

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a pregnancy complication defined as impaired blood sugar regulation beginning in pregnancy, and is no longer present after delivery. Although prevalence varies, a recent study by the CDC reports that as many as 9.2% of pregnancies are affected by gestational diabetes.18 Oct 19 It can be difficult for many women to find and utilize non hormonal options when it comes to fertility. This includes women who want to become pregnant but also those who are looking to avoid pregnancy. With many women and couples having misconceptions regarding the fertile period of a woman’s cycle, it is more advantageous to educate women on their fertile signs for greater chances of either conception or avoidance of conception.[1]05 Jun 14

It can be difficult for many women to find and utilize non hormonal options when it comes to fertility. This includes women who want to become pregnant but also those who are looking to avoid pregnancy. With many women and couples having misconceptions regarding the fertile period of a woman’s cycle, it is more advantageous to educate women on their fertile signs for greater chances of either conception or avoidance of conception.[1]05 Jun 14 Pregnancy can be one of the most exciting times in a woman’s life. It can also be one of the most stressful times, especially if the pregnancy is complicated with health issues. There are many common and familiar “side effects” of pregnancy, such as nausea, heartburn, and fatigue. However, there are also more serious conditions that can develop following pregnancy, and the symptoms should not be ignored or brushed aside, as they can potentially be signs of new disease onset, and could greatly affect long-term health.

20 Sep 19

Pregnancy can be one of the most exciting times in a woman’s life. It can also be one of the most stressful times, especially if the pregnancy is complicated with health issues. There are many common and familiar “side effects” of pregnancy, such as nausea, heartburn, and fatigue. However, there are also more serious conditions that can develop following pregnancy, and the symptoms should not be ignored or brushed aside, as they can potentially be signs of new disease onset, and could greatly affect long-term health.

20 Sep 19 Thinking of conceiving? You may have heard about the “100 days”—the time it takes for an egg to mature. For men, it takes about 80 days for sperm to mature. During this time of development and maturation, a woman’s follicles and a man’s sperm are extremely vulnerable to DNA damage from exposure to toxins, systemic or chronic inflammation, and nutrient deficiencies. This means that for many who are ready to or are thinking of conceiving in the not-so-far future, the health of their eggs and sperm can be greatly impacted before they are even released, either during ovulation or ejaculation. This is the window that we need to take advantage of, to increase the health of our eggs and sperm to increase the odds of a viable and healthy egg, and fertilization.

Thinking of conceiving? You may have heard about the “100 days”—the time it takes for an egg to mature. For men, it takes about 80 days for sperm to mature. During this time of development and maturation, a woman’s follicles and a man’s sperm are extremely vulnerable to DNA damage from exposure to toxins, systemic or chronic inflammation, and nutrient deficiencies. This means that for many who are ready to or are thinking of conceiving in the not-so-far future, the health of their eggs and sperm can be greatly impacted before they are even released, either during ovulation or ejaculation. This is the window that we need to take advantage of, to increase the health of our eggs and sperm to increase the odds of a viable and healthy egg, and fertilization.

Newsletter

Most Popular

- 26 Sep 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13