Related Articles

- 26 Jul 18

In my line of work, many patients come with chronic conditions that affect their quality of life, for which there has been little to no “standard” solution. Symptoms such as slowly worsening fatigue, weight gain, skin rashes, headaches, and joint pain are common complaints.

- 09 Mar 15

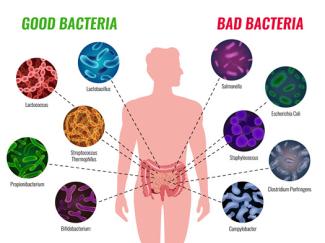

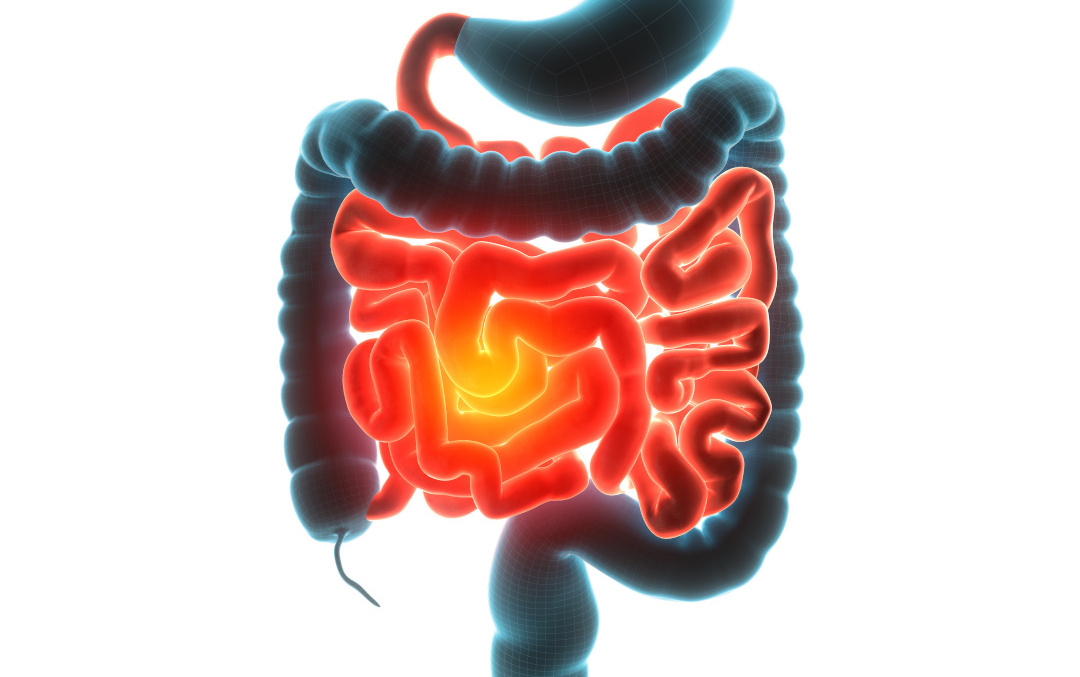

In order to effectively optimize your digestive health, it is imperative that you approach this systematically to ensure long-term results. My four-tiered approach to optimal health is to Remove any possible triggers causing the digestive disturbance in the first place, Repair the intestinal lining, challenge the digestive tract by Reintroducing different food groups and observing the body’s reaction to identify possible food sensitivities, and Reinoculate the healthy bacteria in order to support the body’s immune system and maintain digestive function.

In order to effectively optimize your digestive health, it is imperative that you approach this systematically to ensure long-term results. My four-tiered approach to optimal health is to Remove any possible triggers causing the digestive disturbance in the first place, Repair the intestinal lining, challenge the digestive tract by Reintroducing different food groups and observing the body’s reaction to identify possible food sensitivities, and Reinoculate the healthy bacteria in order to support the body’s immune system and maintain digestive function. - 11 Jul 17

Parkinson’s disease affects between 1–2% of the population over the age of 65 and is becoming a growing concern as the baby boomers advance in age. The condition is characterized by gait abnormalities, tremor, muscle rigidity, and slowing down of movement typically seen as difficulty walking or getting up out of a chair.

Parkinson’s disease affects between 1–2% of the population over the age of 65 and is becoming a growing concern as the baby boomers advance in age. The condition is characterized by gait abnormalities, tremor, muscle rigidity, and slowing down of movement typically seen as difficulty walking or getting up out of a chair. - 08 Jun 15

Probiotics are a popular intervention used by naturopathic doctors in the treatment of these atopic conditions, such as eczema, allergies, and asthma, as well as digestive disorders; in fact, epidemiological evidence has shown children with atopic diseases have different intestinal (probiotic) flora compared to healthy children.

Probiotics are a popular intervention used by naturopathic doctors in the treatment of these atopic conditions, such as eczema, allergies, and asthma, as well as digestive disorders; in fact, epidemiological evidence has shown children with atopic diseases have different intestinal (probiotic) flora compared to healthy children. - 05 Jan 22

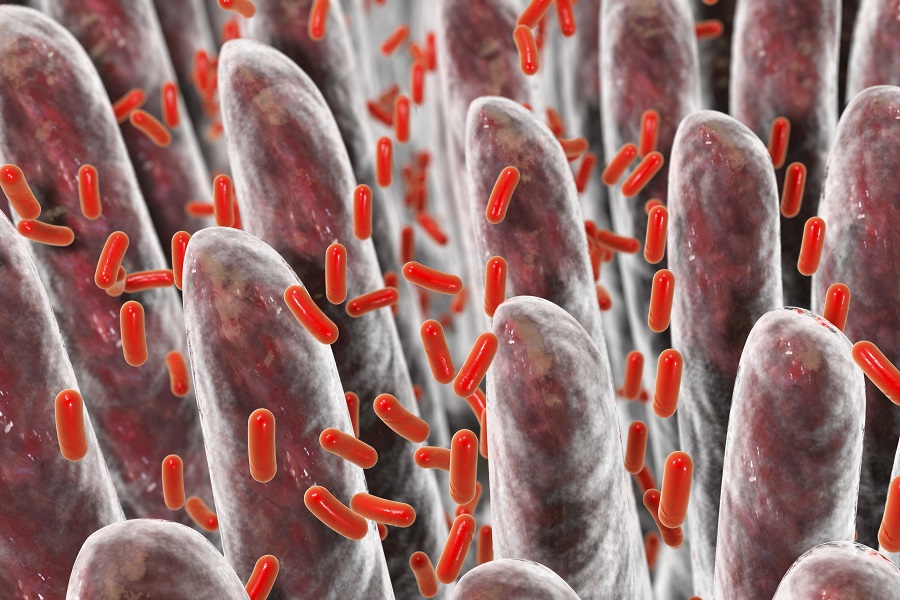

The human digestive tract is a dynamic ecosystem made up of a rich and diverse microbiota consisting of bacteria, archaea, viruses, and fungi. Each person has a unique composition of microbiota, and the balance in this symbiotic relationship must be “respected in order to optimally perform metabolic and immune functions and prevent disease development.

- 30 Apr 19

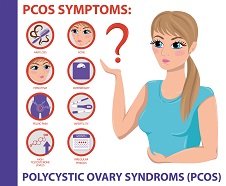

We often think of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) as a hormonal disorder, but it’s also (and maybe even predominantly) a metabolic one.

- 26 Feb 21

In conditions that promote a leaky gut, the compounds of the food bolus that are usually kept safely in the intestinal lumina—including undigested food macromolecules, toxins, bacteria, or parts of bacteria known as endotoxins—has now the potential to pass through the fragile and unicellular mucosal membrane of the small intestine, and to reach the blood circulation.

In conditions that promote a leaky gut, the compounds of the food bolus that are usually kept safely in the intestinal lumina—including undigested food macromolecules, toxins, bacteria, or parts of bacteria known as endotoxins—has now the potential to pass through the fragile and unicellular mucosal membrane of the small intestine, and to reach the blood circulation. - 30 Apr 19

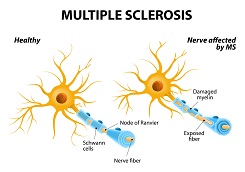

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the result of a series of intricate changes within the body that ultimately lead to rapid decline physically, cognitively, and, of course, emotionally. Let’s look at the stats.

- 02 Jul 14

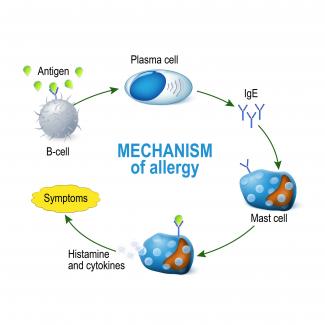

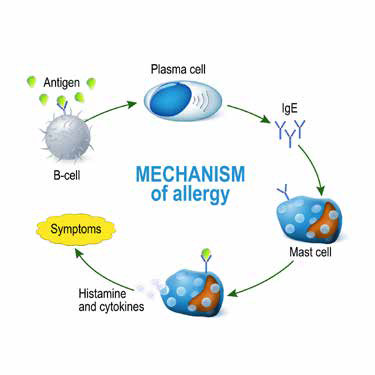

Atopic dermatitis, also known as eczema, is a chronic and/or relapsing inflammatory skin condition, which often begins in childhood and persists into adulthood. According to the World Allergy Association, the term “atopic” refers to the genetic predisposition to develop an allergic reaction and produce IgE antibodies in response to the exposure to an allergen, usually proteins.

01 May 21

Atopic dermatitis, also known as eczema, is a chronic and/or relapsing inflammatory skin condition, which often begins in childhood and persists into adulthood. According to the World Allergy Association, the term “atopic” refers to the genetic predisposition to develop an allergic reaction and produce IgE antibodies in response to the exposure to an allergen, usually proteins.

01 May 21With spring come seasonally grown local foods and green leafy vegetables (GLV) become more desirable for quality, and especially for their overall health benefits. Examples of GLV include salads, kale, broccoli, collard greens, spinach, mustard greens, etc.

03 Jan 14$path = isset($_GET['q']) ? $_GET['q'] : '

';

$link = url($path, array('absolute' => TRUE));$nid = arg(1);

if ($nid == 201401){

?>download pdf

}

?> Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a condition characterized by chronic widespread pain and extreme fatigue. It has long been considered a controversial diagnosis, largely because its pathophysiology is poorly understood. Some have thought it to be a form of malingering, or a psychosomatic condition; others have viewed it as a rheumatologic or neurologic illness.

17 Oct 19

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a condition characterized by chronic widespread pain and extreme fatigue. It has long been considered a controversial diagnosis, largely because its pathophysiology is poorly understood. Some have thought it to be a form of malingering, or a psychosomatic condition; others have viewed it as a rheumatologic or neurologic illness.

17 Oct 19 A cough is one of the most common reasons people visit their doctor. Coughs are annoying, they’re loud and can disrupt sleep for an entire household. With most viral infections, a cough can stick around up to 2 weeks after the infection has cleared. But when a cough lasts longer than 8 weeks, it warrants further investigation.[1]02 Aug 19

A cough is one of the most common reasons people visit their doctor. Coughs are annoying, they’re loud and can disrupt sleep for an entire household. With most viral infections, a cough can stick around up to 2 weeks after the infection has cleared. But when a cough lasts longer than 8 weeks, it warrants further investigation.[1]02 Aug 19 Spring has finally arrived and with it has come lots of sunshine, birds coming out to play, and unfortunately, also a lot of sneezing, runny noses, and congestion. For allergy sufferers, this time of year can be both a blessing and curse. While the most effective way to deal with your allergies is to prepare your body 2-3 months BEFORE "allergy season", there are still ways you can help reduce symptoms. 21 Apr 18

Spring has finally arrived and with it has come lots of sunshine, birds coming out to play, and unfortunately, also a lot of sneezing, runny noses, and congestion. For allergy sufferers, this time of year can be both a blessing and curse. While the most effective way to deal with your allergies is to prepare your body 2-3 months BEFORE "allergy season", there are still ways you can help reduce symptoms. 21 Apr 18Today, most schools are nut-free facilities, and laws have been passed to ensure proper labeling of all ingredients in a product. Still, many families struggle with the idea of keeping certain foods off the dinner table.

19 Sep 19 Naturopathic doctors are holistic practitioners and see the body with all its connections. We believe the basis of all disease and illness begins in the gastrointestinal tract and the organs of detoxification. After all, if the entire tube from your mouth to your rear end is considered the outside of your body, the only way you have access to the food you eat is through the processes of digestion and absorption05 Jul 1906 Dec 18

Naturopathic doctors are holistic practitioners and see the body with all its connections. We believe the basis of all disease and illness begins in the gastrointestinal tract and the organs of detoxification. After all, if the entire tube from your mouth to your rear end is considered the outside of your body, the only way you have access to the food you eat is through the processes of digestion and absorption05 Jul 1906 Dec 18Do you ever feel bloated or constipated? Maybe you experience headaches or skin reactions that appear to have no known cause? Maybe you’re constantly tired, unable to concentrate or focus? The reason for these reactions may surprise you and have you looking no further than your dinner plate.

28 Feb 19A healthy gut is a crucial part of maintaining your overall health. It seems today that many diseases and health concerns have root in an imbalanced gut. The foods we consume, the stresses we experience, and the exposure to toxic elements have created a dysbiosis of the gut. This leads to changes in our moods, our vitality, and our energy. We feel less inclined to get through the day, and most of our day becomes a task rather than anything else.

06 Dec 18Gastrointestinal reflux disease (GERD) is the backwards flow of stomach contents into the esophagus, often referred to as “heartburn” or “acid reflux.” GERD most commonly results from increased abdominal pressure or a dysfunction of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), a bundle of muscles located at the end of the esophagus where it meets the stomach.

31 May 19Acne vulgaris is one of the most common, chronic skin conditions. Up to 80–90% of the population will experience some degree of acne.[1]

Newsletter

Most Popular

- 06 Jan 22

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13