Related Articles

- 09 Mar 20

The viruses that cause colds and the flu can be spread easily by coughing and sneezing. While there is no way to guarantee you won’t get sick this winter, there are things you can do to reduce the severity of your sickness.

- 09 Mar 20

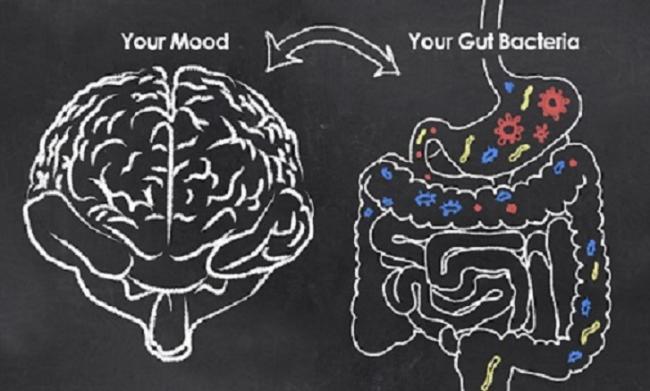

The link between sleep and mental health has been seen and studied for decades by doctors and researchers. People who don’t get their regular 7–9 hours of sleep per night are at 10× greater risk of depression and 17× greater risk of anxiety. To go one step further, the more frequently one wakes in the night due to insomnia, the higher the chances of developing depression.[1] Before considering pharmaceutical sleeping aids, it is important that we consider all aspects of health that can be contributing to a sleep disorder.

- 05 Jun 17

- 13 Apr 17

- 26 Feb 21

Long before February was declared “Heart Month” in Canada, “American Heart Month” in the United States, and “National Heart Month” in the United Kingdom, children and adults celebrated February 14 as a day of love and affection.

- 02 Sep 15

- 02 Aug 19

Something everyone has in common is the need for sleep. We spend about one-third of our lives sleeping. Since we all need sleep, we all have different strategies and techniques in order to ensure a restful night’s sleep. Sleep hygiene are the habits one does in order to try to sleep well on a consistent basis.

- 14 Nov 19

College; it’s sometimes called “the best time in your life.” You have new people, new situations, a huge variety of extracurricular activities to choose from, all while learning about yourself and the world… It is a time full of potential!

- 16 Apr 18

Every time I turn around, someone else has published a news article saying that cell phones are rewiring our brains, stealing our creativity, and making us unable to focus and by some measures, even decreasing our intelligence—but are they really?

- 20 Feb 18

Sleep problems are very common in children. Those between the ages of 2-8 years-old often exhibit snoring or breathing difficulties, which can be a sign of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The main reason for this is due to the size of the adenoids and/or tonsils relative to the diameter of the upper airway at this point of physical development. The consequences of this go beyond being a “noisy” sleeper as apnea ....

- 22 Feb 18

Sleeping disorders are quite common among the population. The term insomnia has been used as a general term in literature and society in a variety of ways to describe sleeping disorders. Insomnia is defined as an individual’s difficulty with sleep or an individual’s dissatisfaction with quality of sleep.

- 11 Mar 16

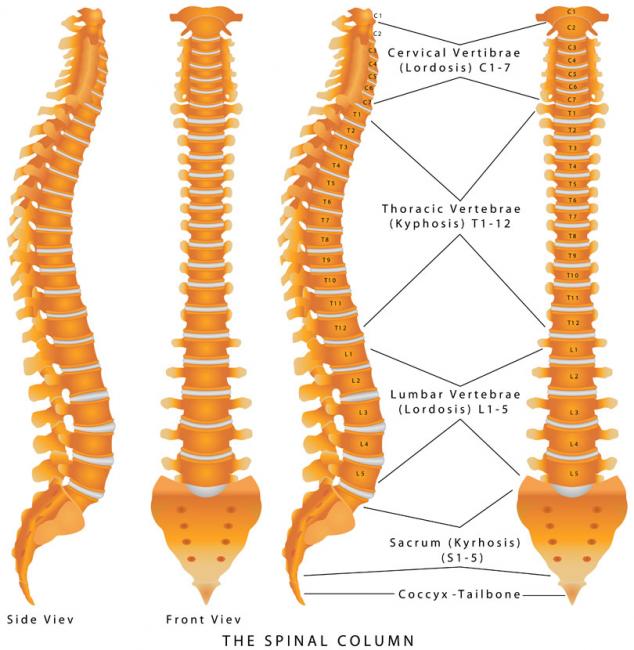

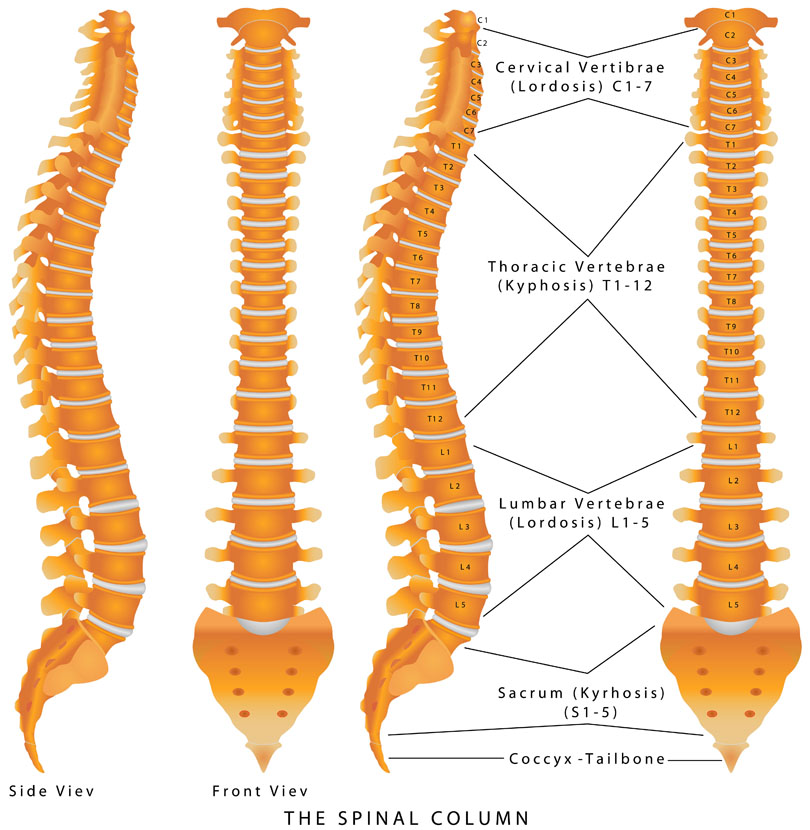

Walk down a busy street and you’ll see some atrocious body language and posture. Most people are hunched over, head down, eyebrows furrowed, and probably typing away on their cell phones. Anybody who is sitting is almost guaranteed to be hunched over: driving, eating, talking, on the phone, going to the toilet, working at a desk, studying, etc.

Walk down a busy street and you’ll see some atrocious body language and posture. Most people are hunched over, head down, eyebrows furrowed, and probably typing away on their cell phones. Anybody who is sitting is almost guaranteed to be hunched over: driving, eating, talking, on the phone, going to the toilet, working at a desk, studying, etc. - 21 Dec 16

- 22 Jan 18

Anxiety is extremely common; in fact, the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention reports that anxiety disorders are the most common class of mental disorders. Aside from the anxiety, 60–70% of people with anxiety also report that they have trouble sleeping. This is problematic, because the worse someone’s emotional distress is the worse they sleep, and having bad sleep may be contributing to worsening anxiety symptoms.

- 01 Oct 22

Attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD) is a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by inattention, impulsiveness, and hyperactivity. The condition is commonly treated with stimulant therapy (methylphenidates or amphetamines in various forms). Stimulants tend to increase dopamine activity in the brain, and it is speculated that this may help with ADHD symptoms.

- 03 Apr 14

Sleeping can be complicated business! Those individuals with no difficulty achieving healthy, regular sleep would think it the simplest of physiologic phenomena. Roughly 30% of the population suffers from insomnia, however,[1] which has real and important health consequences, in addition to affecting quality of life. Even short-term sleep disruption is associated with metabolic problems, insulin insensitivity, poor blood-sugar control, increased body mass index (BMI), increased pain and inflammation levels, and even increased mortality.

03 Jan 14

Sleeping can be complicated business! Those individuals with no difficulty achieving healthy, regular sleep would think it the simplest of physiologic phenomena. Roughly 30% of the population suffers from insomnia, however,[1] which has real and important health consequences, in addition to affecting quality of life. Even short-term sleep disruption is associated with metabolic problems, insulin insensitivity, poor blood-sugar control, increased body mass index (BMI), increased pain and inflammation levels, and even increased mortality.

03 Jan 14$path = isset($_GET['q']) ? $_GET['q'] : '

';

$link = url($path, array('absolute' => TRUE));$nid = arg(1);

if ($nid == 201401){

?>download pdf

}

?> Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a condition characterized by chronic widespread pain and extreme fatigue. It has long been considered a controversial diagnosis, largely because its pathophysiology is poorly understood. Some have thought it to be a form of malingering, or a psychosomatic condition; others have viewed it as a rheumatologic or neurologic illness.

20 Sep 19

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a condition characterized by chronic widespread pain and extreme fatigue. It has long been considered a controversial diagnosis, largely because its pathophysiology is poorly understood. Some have thought it to be a form of malingering, or a psychosomatic condition; others have viewed it as a rheumatologic or neurologic illness.

20 Sep 19 The value of breastmilk continues to grow as we discover additional properties and health benefits. It contains all the nutrients that a newborn requires, except for vitamin D, and life protecting antibodies that are custom made by mom in response to the unique dangers of her environment. However, recent research continues to uncover hidden treasures within this elixir of life. This article will review new studies and discuss the implication for infant development.28 Feb 18

The value of breastmilk continues to grow as we discover additional properties and health benefits. It contains all the nutrients that a newborn requires, except for vitamin D, and life protecting antibodies that are custom made by mom in response to the unique dangers of her environment. However, recent research continues to uncover hidden treasures within this elixir of life. This article will review new studies and discuss the implication for infant development.28 Feb 18Do you find yourself tired in the early evening? This is certainly not uncommon if you have just had an intense workout, eaten a large meal or had an exceptionally exhausting day. However, if you find that you are very tired at an unusually early hour, around 6pm or 7pm, you may be suffering from a sleep disorder known as Advanced Sleep Phase Syndrome (ASPS). ASPS is one of a group of sleep disorders

27 Aug 18According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, as of 2010, the diagnosis of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) applied to roughly 1.4% of the Canadian population aged 12 and over. Unfortunately, because it is often poorly understood by the medical system, it also likely goes undiagnosed in many patients.

Newsletter

Most Popular

- 27 Jan 21

- 07 May 15

- 03 Nov 16

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13