Related Articles

- 25 May 16

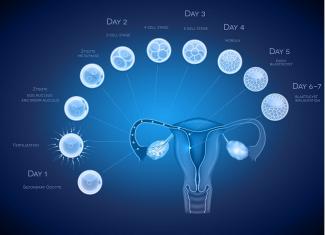

Whether by unmediated naturals means, induction, or caesarean section, the birth of a child can be an exciting, frightening, and overwhelming experience, and all this is just within in the first moments of life! While some birth experiences go on exactly as planned, others are not as routine, and fortunately procedures such as caesarean delivery (CD) are available to those who might otherwise suffer the negative consequences that can be associated with the birthing process.

Whether by unmediated naturals means, induction, or caesarean section, the birth of a child can be an exciting, frightening, and overwhelming experience, and all this is just within in the first moments of life! While some birth experiences go on exactly as planned, others are not as routine, and fortunately procedures such as caesarean delivery (CD) are available to those who might otherwise suffer the negative consequences that can be associated with the birthing process. - 29 Jan 21

After iron, zinc is the most abundant element in the human body, with approximately 2 to 4 g distributed among the muscles (60%), bones (20%), liver, and skin. Given its abundance, concerns about zinc deficiency is often overlooked; however, as discussed in this article, certain populations and individuals may benefit from supplementation.

- 03 Mar 14

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a condition consisting of ovulatory dysfunction and hyperandrogenism, defined as excess activity of testosterone and related androgen hormones. PCOS affects approximately 10% of women of reproductive age, and is a common cause of infertility. However, women with PCOS often suffer from more subtle disturbances in other hormone axes as well, such as thyroid and adrenal systems.

01 Feb 14

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a condition consisting of ovulatory dysfunction and hyperandrogenism, defined as excess activity of testosterone and related androgen hormones. PCOS affects approximately 10% of women of reproductive age, and is a common cause of infertility. However, women with PCOS often suffer from more subtle disturbances in other hormone axes as well, such as thyroid and adrenal systems.

01 Feb 14$path = isset($_GET['q']) ? $_GET['q'] : '

';

$link = url($path, array('absolute' => TRUE));$nid = arg(1);

if ($nid == 201402){

?>download pdf

}

?> Resveratrol is an important phytonutrient and antioxidant that naturally occurs in the skin of red grapes, peanuts, and some berries, and is touted as the health-promoting compound found in red wine. In the last few years, resveratrol research has exploded. Well over 1,000 research papers have been written to examine the health benefits of this plant compound in the past two years alone.

16 Jan 16

Resveratrol is an important phytonutrient and antioxidant that naturally occurs in the skin of red grapes, peanuts, and some berries, and is touted as the health-promoting compound found in red wine. In the last few years, resveratrol research has exploded. Well over 1,000 research papers have been written to examine the health benefits of this plant compound in the past two years alone.

16 Jan 16 Among all sexual dysfunctions, erectile dysfunction (ED) is the most common [1]. Approximately 1 in 10 men worldwide have ED, the prevalence ranging from 10-71% for men older than 70 years old [2]. This range is so wide and there are no reliable figures available for the incidence and prevalence of ED because most men do not seek treatment. Social stigma is all too familiar and continues to be a reality for men suffering with erectile dysfunction (ED), this being the biggest barrier to them seeking treatment.04 Oct 1703 Feb 15

Among all sexual dysfunctions, erectile dysfunction (ED) is the most common [1]. Approximately 1 in 10 men worldwide have ED, the prevalence ranging from 10-71% for men older than 70 years old [2]. This range is so wide and there are no reliable figures available for the incidence and prevalence of ED because most men do not seek treatment. Social stigma is all too familiar and continues to be a reality for men suffering with erectile dysfunction (ED), this being the biggest barrier to them seeking treatment.04 Oct 1703 Feb 15 Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a pregnancy complication defined as impaired blood sugar regulation beginning in pregnancy, and is no longer present after delivery. Although prevalence varies, a recent study by the CDC reports that as many as 9.2% of pregnancies are affected by gestational diabetes.11 Jul 1708 Jun 15

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a pregnancy complication defined as impaired blood sugar regulation beginning in pregnancy, and is no longer present after delivery. Although prevalence varies, a recent study by the CDC reports that as many as 9.2% of pregnancies are affected by gestational diabetes.11 Jul 1708 Jun 15 Probiotics are a popular intervention used by naturopathic doctors in the treatment of these atopic conditions, such as eczema, allergies, and asthma, as well as digestive disorders; in fact, epidemiological evidence has shown children with atopic diseases have different intestinal (probiotic) flora compared to healthy children.03 May 1725 May 16

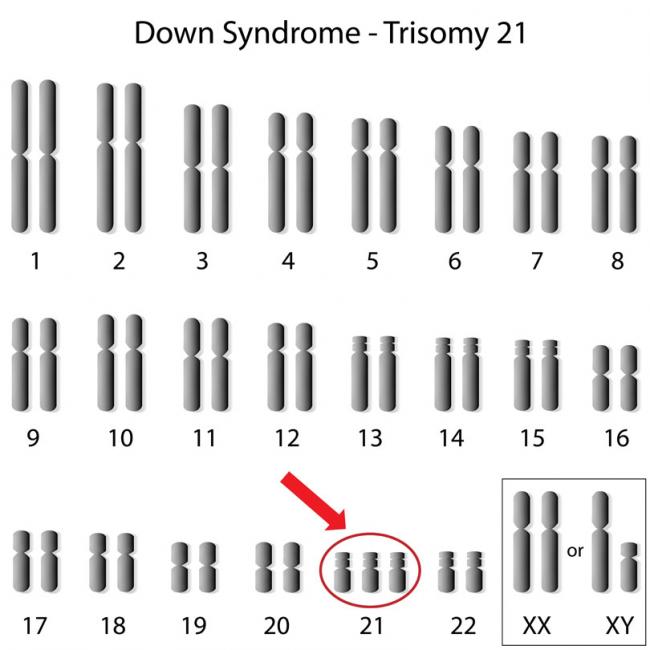

Probiotics are a popular intervention used by naturopathic doctors in the treatment of these atopic conditions, such as eczema, allergies, and asthma, as well as digestive disorders; in fact, epidemiological evidence has shown children with atopic diseases have different intestinal (probiotic) flora compared to healthy children.03 May 1725 May 16Down syndrome received its name in 1866, when John Langdon Down initially described this disorder. Down syndrome is more recently known as trisomy 21 (T21), which better describes the extra 21st chromosome that is distinctive for 95% of individuals with this genetic disorder.

14 Jun 18The availability of contraceptive birth control has been incredibly supportive of women’s autonomy over reproductive health. As women, we’ve been given this amazing opportunity to be in control of our bodies; whether it be for preventing an accidental pregnancy, or for obtaining relief from hormonal dysfunction.

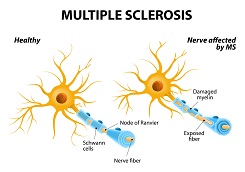

07 Feb 18In media today, inflammation is depicted as having a negative influence on health but for good reason. Inflammation is related to many disease processes especially those involved in auto-immune conditions such as Crohn’s disease, arthritis; asthma (1). It is easy to forget that the inflammatory response as part of the immune system is itself an adaptive process to aid in healing.

06 Sep 1603 May 1726 Aug 13An emerging area of study is dedicated to studying the impact of early life factors including nutrition on the development of disease later on in life. The fetal origins of adult disease (FOAD) are a field devoted to investigating the link between maternal/fetal conditions during prenatal life, and chronic disease risk in adult life. Although this makes intuitive sense, the extent of its influence was not realized until relatively recently.

26 Aug 13$path = isset($_GET['q']) ? $_GET['q'] : '

';

$link = url($path, array('absolute' => TRUE));$nid = arg(1);

if ($nid == 201308){

?>download pdf

}

?>

Menstrual concerns are common problem in women’s health, encompassing a wide range of concerns including premenstrual syndrome (PMS), painful menstruation (dysmenorrhea), and irregular or absent periods (amenorrhea). These symptoms can be a part of several medical conditions including polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, and uterine fibroids. Although not life-threatening, these health issues negatively impact the quality of a woman’s life and signal unresolved underlying problems.26 Sep 13

Insulin resistance is a common condition, affecting 10% of young adults and nearly 44% of adults in mid-life. It is now known that genetic factors play a role in insulin resistance. Diet, body composition, and exercise levels are also major causes, explaining the growing incidence of this disorder with modern lifestyles. Interestingly, insulin resistance may also contribute to infertility01 Oct 13$path = isset($_GET['q']) ? $_GET['q'] : '

';

$link = url($path, array('absolute' => TRUE));$nid = arg(1);

if ($nid == 201310){

?>download pdf

}

?>

While becoming pregnant is wonderful news, especially for couples who have faced fertility challenges, it is only the beginning of the journey. Unfortunately not all pregnancies are 40 weeks of smooth sailing. Some women are faced with more serious concerns such as vaginal bleeding (and therefore presumed threatened miscarriages) giving rise to much stress and anxiety, while others suffer from severe nausea/vomiting.

Newsletter

Most Popular

- 18 Oct 19

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13