Related Articles

- 09 Mar 20

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a type of depression that is only present during the winter months. This differs from clinical depression, which has no seasonal pattern. SAD also tends to improve when the springtime occurs.

- 29 Jan 24

The article explores how dietary choices impact anxiety, from breakfast habits to macronutrients like carbohydrates and proteins. It also highlights the role of gut health and gluten sensitivity in mental wellbeing.

- 29 Apr 22

Probiotics have extensive potential for therapeutic use, and we continue to discover their specific actions. The previous article looked at classification and the role of probiotics with regards to immune function and digestion, including autoimmunity, atopic skin reactions, and respiratory conditions.

- 17 Dec 19

Sadness, hopelessness and loss of interest in previously interesting activities are the hallmark of a serious, well-known mood disorder commonly referred to as depression. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) defines the disorder based on specific emotions that one must feel for a set amount of time.

- 16 Dec 19

In many parts of the world, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is not a common diagnosis. But in North America, a large portion of the pediatric population is being screened and diagnosed with ADHD every day. While there are differences in culture and diet, could there be more that we are missing in our understanding of this developmental condition?

- 05 May 20

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) is a pandemic that has affected more than 200 countries all around the world, according to the World Health Organization. This disease outbreak, which started in January 2020, has shocked the world due to its uncontrollable spread and increasing death rate. Social isolation, reduced financial ability, and the lack of certainty about the future may cause symptoms of anxiety and depression in many individuals during this period. Amidst all this, many are worried about their own health status or the health of their loved ones.

- 10 Jun 20

Depression and anxiety deplete your energy, desire, and hope. They make it difficult for you to take a step that can help you to feel better. Depression is the second most frequent medical condition seen in common medical practice around the world; it is caused by alterations of the neurotransmitters in our central nervous system.[1] It is a mood disorder that occurs differently in different individuals.

- 09 Mar 20

The human gastrointestinal tract (GIT) alone contains 1014 microorganisms including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. That’s approximately 100 times more microbial cells than human cells, which shows how much of an impact they can have on human health.

- 09 Jan 20

In an ever-evolving and modernizing world, we often overlook some of the simplest things. Many cultures are based around certain foods and religious values that teach a way of life. In these cultures, practising these religious values creates a sense of community that binds the group together and further emphasizes the culture. But as families move to new cities and countries, holding on to that cultural upbringing that includes religion becomes harder and harder.

- 10 Jun 20

Growing up with both parents in the teaching profession, over the years, I’ve grown accustomed to hearing commentary on “kids these days.” Lately, the conversation seems to centre around “anxious kids” or childhood anxiety. Not only do my parents see this in schools, but I hear about it all the time in my naturopathic practice from parents and even children themselves. The stats also seem to be in agreement.

- 09 Mar 20

The link between sleep and mental health has been seen and studied for decades by doctors and researchers. People who don’t get their regular 7–9 hours of sleep per night are at 10× greater risk of depression and 17× greater risk of anxiety. To go one step further, the more frequently one wakes in the night due to insomnia, the higher the chances of developing depression.[1] Before considering pharmaceutical sleeping aids, it is important that we consider all aspects of health that can be contributing to a sleep disorder.

- 08 Jul 20

Anxiety is a very common mental-health disorder and can have implications on all aspects of one’s life. This may come from a variety of factors such as finances, relationships, health, and more. Anxiety lends itself well to natural treatments such as herbal medicine, supplements, and lifestyle modification

- 05 May 20

Do you ever question if your health is being helped or hindered by technology? With modern technology advancing, there is a diminished need to leave your home, let alone get off your couch.

- 08 Jul 20

As the COVID-19 pandemic seemed to shut down the world, grocery stores, or at least what was left on the shelves at grocery stores, became an indicator of where people were at in their experience of the stressful event.

- 18 Dec 17

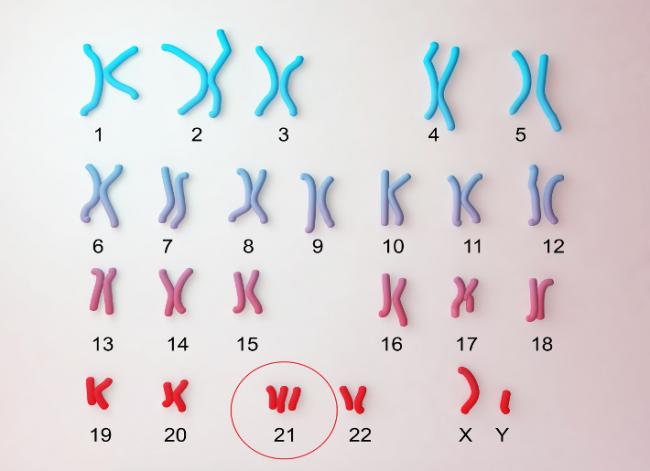

About seventy percent of children with T21 will have vision problems. Nearsightedness, farsightedness, and crossed eyes (strabismus) are the common visual disturbances found in children with T21. As a result, annual vision tests are very important for children with T21. Most of the conditions mentioned in the previous part of this article (https://www.naturopathiccurrents.com/articles/down-syndrome) are easily correctable.

- 01 Feb 14

$path = isset($_GET['q']) ? $_GET['q'] : '

';

$link = url($path, array('absolute' => TRUE));$nid = arg(1);

if ($nid == 201402){

?>download pdf

}

?> Many readers will be aware of an ongoing public debate regarding the validity of naturopathic medicine. The debate often centers on the existence of evidence to support the safety and effectiveness of naturopathic medicine. In this article, we throw new light on the state of naturopathic medicine research and highlight the oft-overlooked body of evidence that already exists.

01 Feb 14

Many readers will be aware of an ongoing public debate regarding the validity of naturopathic medicine. The debate often centers on the existence of evidence to support the safety and effectiveness of naturopathic medicine. In this article, we throw new light on the state of naturopathic medicine research and highlight the oft-overlooked body of evidence that already exists.

01 Feb 14With the growing prevalence of cognitive decline, there is a need for sustainable lifestyle interventions to support, maintain, and improve cognitive health. As physical exercise bolsters bodily health, so too is there a need for mental training. The evolution of technology offers new, promising mediums for cognitive training. This medium is the realm of virtual reality, video games, and mobile devices, that allow for the development of individualized training regimes tailored to suit the person’s needs.

26 Feb 21Long before February was declared “Heart Month” in Canada, “American Heart Month” in the United States, and “National Heart Month” in the United Kingdom, children and adults celebrated February 14 as a day of love and affection.

17 Aug 1607 May 15 Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) is the medical name for anxiety. Everyone worries about important things in life, such as family, work, and health. People who have GAD are extremely worried about these and other smaller things, even when there is little reason to worry about them. There are multiple ways in which the worrying of GAD is worse. The first is the intensity of the worry.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) is the medical name for anxiety. Everyone worries about important things in life, such as family, work, and health. People who have GAD are extremely worried about these and other smaller things, even when there is little reason to worry about them. There are multiple ways in which the worrying of GAD is worse. The first is the intensity of the worry.

Newsletter

Most Popular

- 07 May 15

- 08 Jan 15

- 26 Sep 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13