Persistent Depressive Disorder - The Emotional Equivalent of Watching Paint Dry

Sadness, hopelessness and loss of interest in previously interesting activities are the hallmark of a serious, well-known mood disorder commonly referred to as depression. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) defines the disorder based on specific emotions that one must feel for a set amount of time. Depressed mood, diminished pleasure, and feelings of worthlessness are a few of the criteria that must be felt for at least two continuous weeks for someone to be diagnosed with depression, clinically known as major depressive disorder (MDD).[1] Thanks to the efforts of suicide-prevention programs, depression is generally known to the public in one way or the other. One, hidden, less-commonly addressed form of depression is persistent depressive disorder (PDD). The criteria for being diagnosed with PDD includes milder symptoms of MDD with a persistence of at least two years. Due to being less severe than MDD, PDD is usually overlooked or minimized.[2]

PDD v. MDD

In some ways, PDD can be just as severe as MDD and can significantly affect the quality of life of the affected individual. Compared to MDD, those suffering of PDD do not know or remember what it is like to feel undepressed. They go on for months and years even, without experiencing the excitement and joy that those with normal baseline mood can experience.[3] Unfortunately, those with PDD seldom seek treatment, as their symptoms tend to not be debilitating. Though affecting their everyday life, PDD appears more as a form of a consistent gloomy attitude. Even more concerning, in children, PDD presents itself as a form of irritability, frustration, and failure to meet social demands. Generally, the condition is mild enough for the sufferer to meet the demands of everyday life.[4][5] The sufferers, however, do so without having the capacity to experience joy, excitement, and hope as a nonaffected individual should.

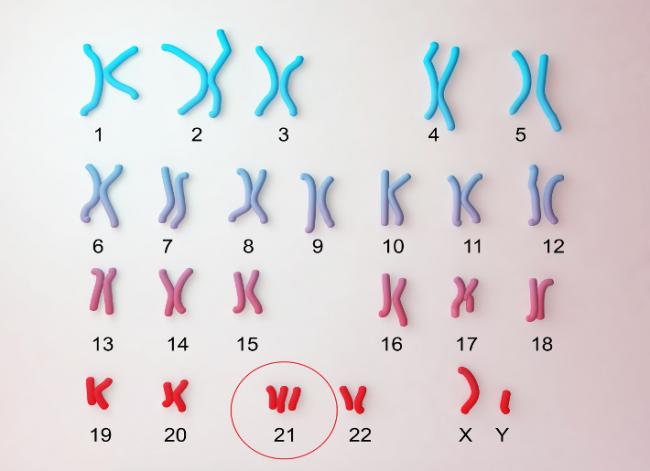

The journey with PDD is usually a very long one, as it takes two years of consistent low-grade depression for the individual to meet the criteria of PDD. During the period, the symptoms should be persistent and should not subside for more than two months at a time. Sleep problems, appetite changes, and a general feeling of frustration are some of the less obvious symptoms related to PDD. PDD may affect individuals at any age and may coexist with MDD, a condition classified by some professionals as double depression.[6][7]

Conventional Treatment Options

PDD is not as severe or life-threatening as MDD. It is, however, a serious mood disorder that chips away at the quality of life little by little. Treatment with mood-enhancing medications may be warranted, but not for all cases. Keeping in mind that mood-enhancing medications can have serious side effects and that some of the greatest mood enhancers can come naturally, it may be worth it to try a natural approach.

Some of the most common medications used for the treatment of PDD include tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors.[8] One of the best conventional treatments for PDD is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT is a method in which thought patterns are examined closely with a trained professional. The positive patterns are enhanced, while the negative patterns are investigated, questioned, and finally replaced by the affected individual with more positive ones. Evidence shows that CBT can enhance treatment and may even cure PDD and MDD.[9][10]

Evidence-Based Approach to Gradual Recovery

On average, it takes individuals affected by depression about 10 years to seek treatment. That is a diminished quality of life that spans over an average of about one eighth of the individual’s lifetime. The first step towards recovery is to question the current state of mood one has. It is important to understand that the journey towards recovery is most likely a gradual, slow-paced one, as PDD is a chronic disorder.[11][12]

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a practice that can vary vastly depending on the practitioner. Many use the term to refer to the practice of meditation for a set amount of time daily. Research shows that mindfulness and meditation can positively impact many physical and emotional aspects of wellbeing. Evidence shows that mindfulness can even increase overall immunity and enhance health.[13] Due to the fact that mindfulness is a practice that requires training and patience, it is best to start mindfulness slowly.[14]

The first step towards being able to practice mindfulness is in practicing awareness. Going on with the normal daily routine with the attempt to be present as events unfold can enhance our understanding of ourselves and our needs. Attempt to clear your mind and always be in the present situation. Take mental or even physical notes of your daily activities. Notice your emotions and your daily reactions to stressor and life demands. A normal individual should experience varying emotions throughout the day. Take note of mental distractors such as anxieties that occupy your mind during the present situation or even positive emotions that keep you in anticipation. Ideally, even a stressful day should have at least one joyful aspect to it.[15]

In the case that you feel your emotions being flat or unresponsive to changes in your present situation, think of the last time you felt true happiness. Examine your personal relationships and your relationship with yourself with the same kind of mindfulness. Isolate the voice in your head and try to find consistencies in the patterns of how you internally view yourself. It is very important to go on exploring your daily life without judgment or effort to change. Remember that you are only collecting data to present your case with self-awareness in the case that you need help from a health-care practitioner.[16]

Balance

While examining your mood, examine your overall life. Start with the way you divide your time. Write down the normal activities you do throughout your day for a week, and rate how joyful each is. Also notice how your day unfolds. Is your sleep balanced? Do you struggle getting out of bed? Do you have a hard time sleeping?[17] Notice your diet: Do you spend time making your food? Do you have a problem overeating or underrating? Have you always had the problem?[18] Are your activities mostly serious? Do you try to get by without doing anything extra? Do you avoid social activities?[19] Are you spiritually satisfied? Do you have a form of spiritual practice? Does your day include any physical activity? Finally, do you struggle to finish all the required tasks in your day?[20] These questions are important ones to ask prior to seeking medical help, as they can assist any practitioner into ruling out physical causes of depression. They can also help build a guideline as to where medical practitioners can start to create a healthy environment for mood enhancement. For example, imbalance in the normal sleep-wake cycle, lack of nourishment with healthy building blocks, and lack of physical activity can all affect mood negatively. Evidence shows that improving such aspects can easily enhance mood and may even solve the underlying problem.[21][22][23]

Important Questions to Ask: Presenting Findings to a Health-Care Practitioner

When you collect information about your situation, know that your relationship with any health-care provider allows you to ask questions and present ideas. It is permitted and highly encouraged for you to speak about how you feel. Present the picture you see with as much detail as possible, and allow your health-care provider to provide you with ideas. In the case that you do not find yourself understood, it is encouraged you seek a second opinion.

Presenting Your Findings

Present your findings to a health-care practitioner and aim first to restore balance. The aim is to gently shift the quality of life in order to have enough space to recover mood. Focus on the basics including food, sleep, and physical activity. Take the advice of your health-care practitioner as to what kind of food, sleep, and physical-activity patterns best suit your body type and life. Ideally, you want to create physical balance and check for other possible causes of depression including—but not limited to—thyroid health, hormone balance, heart health, and metabolic issues.[24]

Balancing Life

Upon securing a general state of balance, it is important to navigate emotional health with a well-trained practitioner. This area is difficult to navigate alone, as one of the most significant problems in mood comes from perception. Consider starting CBT with a trained professional, as evidence shows that CBT remains the gold standard for treating depression.[25]

Seeking Natural Enhancement

As you make the lasting lifestyle changes, you can choose to use some enhancers that can help you balance your life depending on the problem you have a hard time with. Your naturopathic physician can provide you with gentle support that enhances your recovery.

Stress—Evidence shows that the ability to adapt to stress highly affects mood. Reacting to stress with resentment and anxiety is highly linked to depression. Some highly effective adaptogens include:

Panax ginseng: Enhances the physical capacity to deal with stress;[26]

Rhodiola rosea: Enhances the mental capacity to deal with stress;[27] and

Eleutherococcus senticosus: Enhances the immune capacity of the body to act under stress.[28]

It is important to note that some adaptogens can increase blood pressure and must be administered and followed up with a health-care provider.

Sleep—One of the best ways to deal with stress is to normalize the circadian rhythm, which is the sleep-wake cycle. The upkeep of restful sleep can be maintained with supplements including:

Melatonin: A safe, non–habit-forming natural hormone that supports healthy sleep;[29]

Scutellaria lateriflora: A botanical supplement that enhances relaxation and may help initiate sleep;[30] and

Valeriana officinalis: A botanical supplement that initiates and enhances sleep.[31]:228

Mood Balance—One of the best ways to enhance mood is to provide the body with the healthy building blocks required for neurotransmitter synthesis. Neurotransmitters are the signaling molecules that make us feel joy and satisfaction. They drive most of our basic functions and reward us to continue daily activities.

S‑Adenosylmethonine: Evidence shows that the building block S‑adenosylmethonine is as effective as tricyclic antidepressants in enhancing mood;[32]

Niacin is from the B family of vitamins, is also a neurotransmitter building block and shows evidence of mood enhancement. It also regulates mental function, even in some severe mental disorders.[33]

Hypericum perforatum: A mood-enhancing botanical that is backed up by evidence demonstrating effectiveness comparable to conventional serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors, with fewer side effects. It is thought to act as a neurotransmitter enhancer and receptor multiplier.[34]

Please note that standard medications and natural supplements may interact with the previously mentioned natural supplements. It is important to seek the help of a health-care provider when taking supplements. Always remember to never get discouraged. Treating a chronic mood disorder like PDD takes time and hard work, but a joyful life is always worth the effort.

References

[1] Haro, J.M., et al. “Patient-reported depression severity and cognitive symptoms as determinants of functioning in patients with major depressive disorder: a secondary analysis of the 2‑year prospective PERFORM study.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Vol. 15 (2019): 2313–2323.

[2] Kriston, L., et al. “Efficacy and acceptability of acute treatments for persistent depressive disorder: a network meta-analysis.” Depression and Anxiety, Vol. 31, No. 8 (2014): 621–630.

[3] Uher, R., et al. “Major depressive disorder in DSM‑5: implications for clinical practice and research of changes from DSM‑IV.” Depression and Anxiety, Vol. 31, No. 6 (2013): 459–471.

[4] Kriston et al., op. cit.

[5] Uher et al., op. cit.

[6] Uher et al., op. cit.

[7] Barkow, K., et al. “Risk factors for depression at 12‑month follow‑up in adult primary health care patients with major depression: an international prospective study.” Journal of Affective disorders, Vol. 76, No. 1–3 (2003): 157–169.

[8] Gilchrist, G., and J. Gunn. “Observational studies of depression in primary care: what do we know?” BMC Family Practice, Vol. 8 (2007): 28.

[9] Leichsenring, F., and C. Steinert. “Is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy the Gold Standard for Psychotherapy?: The Need for Plurality in Treatment and Research.” JAMA, Vol. 318, No. 14 (2017): 1323–1324

[10] Cuijpers, P., et al. “Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Mental Health Problems: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis.” The American Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 173, No. 7 (2016): 680–687.

[11] Kriston, et al., op. cit.

[12] Uher, et al., op. cit.

[13] Hawley, L.L., et al. “Mindfulness Practice, Rumination and Clinical Outcome in Mindfulness-Based Treatment.” Cognitive Therapy and Research, Vol. 38, No. 1 (2014): 1–9.

[14] Davidson, R.J., et al. “Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation.” Psychosomatic Medicine, Vol. 65, No. 4 (2003): 564–570.

[15] Anālayo, B. “Early Buddhist Mindfulness and Memory, the Body, and Pain.” Mindfulness, Vol. 7, No. 6 (2016): 1271–1280.

[16] Kriston, et al., op. cit.

[17] Troxel, W.M., et al. “Insomnia and objectively measured sleep disturbances predict treatment outcome in depressed patients treated with psychotherapy or psychotherapy-pharmacotherapy combinations.” The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 73, No. 4 (2012): 478–485.

[18] Felton, J., et al. “The relation of weight change to depressive symptoms in adolescence.” Development and Psychopathology, Vol. 22, No. (2010): 205–216.

[19] Uher, et al., op. cit.

[20] Uher, et al., op. cit.

[21] Troxel, et al., op. cit.

[22] Felton, et al., op. cit.

[23] Boschloo, L., et al. “The impact of lifestyle factors on the 2‑year course of depressive and/or anxiety disorders.” Journal of Affective Disorders, Vol. 159 (2014): 73–79.

[24] Boschloo, et al., op. cit.

[25] Leichsenring and Steinert, op. cit.

[26] Panossian, A. “Understanding adaptogenic activity: specificity of the pharmacological action of adaptogens and other phytochemicals.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 1401, No. 1 (2017): 49–64.

[27] Chen, S.P., et al. “Complementary usage of Rhodiola crenulata (L.) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: the effects on cytokines and T cells.” Phytotherapy Research, Vol. 29, No. 4 (2015): 518–525.

[28] Kropotov, A., O. Kolodnyak, and V. Koldaev. “Effects of Siberian ginseng extract and ipriflavone on the development of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.” Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine, Vol. 133, No. 3 (2002): 252–254.

[29] Cardinali, D.P., et al. “Melatonin and its analogs in insomnia and depression.” Journal of Pineal Research, Vol. 52, No. 4 (2012): 365–373.

[30] Xu, Z., et al. “Anxiolytic-Like Effect of baicalin and its additivity with other anxiolytics.” Planta Medica, Vol. 72, No. 2 (2006): 187–189.

[31] Rafinesque, C.S. Medical Flora: or, Manual of Medical Botany of the United States of North America. Philadelphia: Atkinson and Alexander, 1830.

[32] Muskin, P.R., P.L. Gerbarg, and R.P. Brown. “Along roads less traveled: Complementary, alternative, and integrative treatments.” The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, Vol. 36, No. 1 (2013): xiii–xv.

[33] Oxenkrug, G.F. “Tryptophan kynurenine metabolism as a common mediator of genetic and environmental impacts in major depressive disorder: the serotonin hypothesis revisited 40 years later.” The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, Vol. 47, No. 1 (2010): 56–63.

[34] Hypericum Depression Trial Study Group. “Effect of Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort) in major depressive disorder: A randomized controlled trial.” JAMA, Vol. 287, No. 14 (2002): 1807–1814.