Related Articles

- 27 Jan 21Emerging health implications of gluten sensitivity reach far beyond the borders of the gastrointestinal tract. The gluten-sensitive spectrum includes different forms of manifestations: allergic (wheat allergy), autoimmune celiac disease (CD), dermatitis herpetiformis, gluten ataxia, and immune-mediated (nonceliac gluten sensitivity).

- 17 Dec 19

Hitting the hay, sawing logs, catching ZZZs— these are terms we use to describe sleep, but what is happening is more like a well-timed orchestra performance. Areas of the brain work in concert; some turn on and some turn off, directed by cues from light and chemical messengers called neurotransmitters. However, recent research suggests that sleep is not a process confined to the brain but that can receive input from the entire body, most prominently through the immune system.

- 13 Apr 20

Have you met the people that tell you, quite proudly, they never, ever, ever get sick? Do you find yourself feeling just a wee bit jealous? Well, feel jealous no more! Exercising our immune system with a good fever may feel yucky, but it is great for all kinds of reasons.

- 09 Mar 20

The human gastrointestinal tract (GIT) alone contains 1014 microorganisms including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. That’s approximately 100 times more microbial cells than human cells, which shows how much of an impact they can have on human health.

- 02 Jul 14

Consumption of wheat has increased dramatically over the last decades. Wheat was once thought to be an important part of a healthy diet, but now is seen as a potential health threat for many individuals. Gluten is a food component found in wheat, rye, barley, and cereals. More specifically, it is a protein complex that is formed by gliadin and glutenin, typically used in processed foods as a stabilizing agent. Celiac disease (CD) is a complex chronic immune-mediated disorder whose gastrointestinal symptoms are triggered by eating gluten.

13 Apr 1706 Oct 1603 May 1713 Feb 16

Consumption of wheat has increased dramatically over the last decades. Wheat was once thought to be an important part of a healthy diet, but now is seen as a potential health threat for many individuals. Gluten is a food component found in wheat, rye, barley, and cereals. More specifically, it is a protein complex that is formed by gliadin and glutenin, typically used in processed foods as a stabilizing agent. Celiac disease (CD) is a complex chronic immune-mediated disorder whose gastrointestinal symptoms are triggered by eating gluten.

13 Apr 1706 Oct 1603 May 1713 Feb 16 Noticing blood while brushing or flossing can be alarming and shouldn’t be ignored! The importance of oral health is a concept introduced to most Canadians at a very young age, and with good reason. The Ontario Dental Hygienist’s Association reports that the link between oral infections and other diseases in the body is becoming well-documented and accepted within the health-care community. Periodontal disease is one of the most common human diseases02 Sep 1517 Jun 16

Noticing blood while brushing or flossing can be alarming and shouldn’t be ignored! The importance of oral health is a concept introduced to most Canadians at a very young age, and with good reason. The Ontario Dental Hygienist’s Association reports that the link between oral infections and other diseases in the body is becoming well-documented and accepted within the health-care community. Periodontal disease is one of the most common human diseases02 Sep 1517 Jun 16 The use of complementary medicine for the treatment of cancer and its side effects has skyrocketed in recent years. Complementary therapies refer to ones that are nonpharmaceutical in nature, and that have the potential to not only enhance quality of life, but also to reduce side effects of conventional therapy.09 Jul 15

The use of complementary medicine for the treatment of cancer and its side effects has skyrocketed in recent years. Complementary therapies refer to ones that are nonpharmaceutical in nature, and that have the potential to not only enhance quality of life, but also to reduce side effects of conventional therapy.09 Jul 15 W. somnifera, also known as Ashwagandha, is an important herb that has been used for over 3000 years. The important constituents of the root are steroidal alkaloids and steroidal lactones referred to as withanolides. It is used for anxiety, inflammation, Parkinson’s disease, cognitive and neurological disorders, and as a supportive adjunct for people undergoing radiation and chemotherapy.07 May 15

W. somnifera, also known as Ashwagandha, is an important herb that has been used for over 3000 years. The important constituents of the root are steroidal alkaloids and steroidal lactones referred to as withanolides. It is used for anxiety, inflammation, Parkinson’s disease, cognitive and neurological disorders, and as a supportive adjunct for people undergoing radiation and chemotherapy.07 May 15 The immune system is able to discriminate self from non-self antigens, substances that trigger the immune system, which protects the host from infections and cancer. Autoimmune diseases are characterized by deregulated immune responses. Autoimmune diseases affect 5-8% of the population in the United States and can affect almost every site in the body11 Oct 18

The immune system is able to discriminate self from non-self antigens, substances that trigger the immune system, which protects the host from infections and cancer. Autoimmune diseases are characterized by deregulated immune responses. Autoimmune diseases affect 5-8% of the population in the United States and can affect almost every site in the body11 Oct 18A fairly common chronic condition that afflicts people is rheumatoid arthritis (RA); a form of chronic joint inflammation that can have major impact on quality of life. The exact cause of rheumatoid arthritis is unknown, but it has a significant autoimmune component. This is how it differs starkly from the much more common osteoarthritis, which is more of a “wear-and-tear” form of arthritis that results from mechanical use of joints over a long and active life. Rheumatoid arthritis not only affects the joints, but also presents with systemic inflammatory symptoms.

18 Jan 19A large portion of people who see naturopathic doctors come with a chief concern of digestive issues. After months of scopes and bloodwork, they are often left without answers from their medical doctor and seek a new perspective. Other times, their diagnostic imaging tests reveal something significant, yet the medical system is still at a loss for treatment options.

22 Dec 1628 Feb 19Chronic pain is a significant health issue, and it is estimated that one-half of those suffering with chronic pain have been suffering for longer than 10 years.[1] An estimated 54.4 million North Americans have been diagnosed with various arthritic disorders,[2] conditions that are typically treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

08 Jan 15 If you have taken an active interest in your own health-care treatment, then you have likely heard about the benefits of meditation and mindfulness. But do you really know why regular meditation is so beneficial? Common self-reported benefits include reduced levels of anxiety, depression and pain; data which have been reinforced through many clinical trials.10 Apr 1611 Sep 14

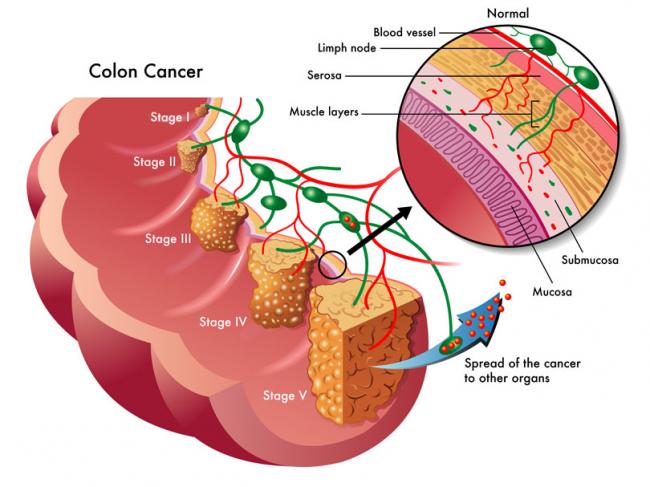

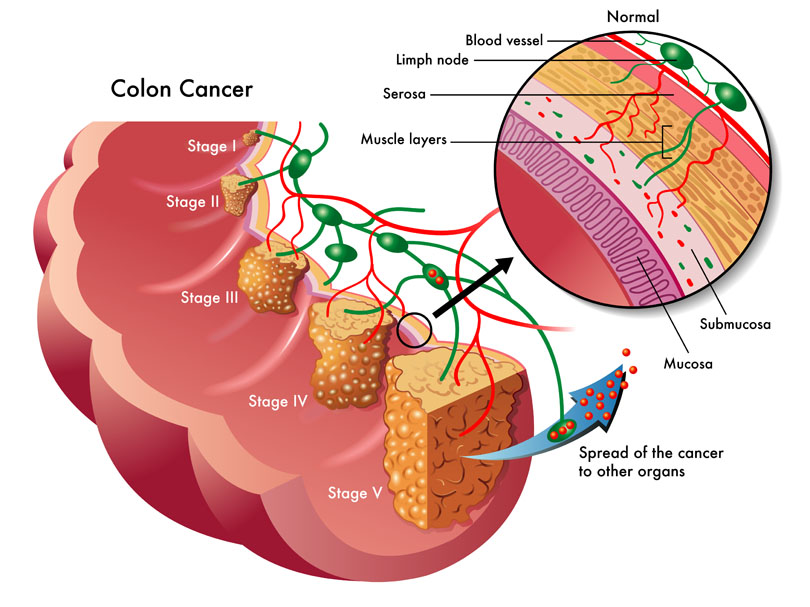

If you have taken an active interest in your own health-care treatment, then you have likely heard about the benefits of meditation and mindfulness. But do you really know why regular meditation is so beneficial? Common self-reported benefits include reduced levels of anxiety, depression and pain; data which have been reinforced through many clinical trials.10 Apr 1611 Sep 14Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) causes extensive inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract causing multiple symptoms, most commonly chronic diarrhea. IBD has periods of flare ups during which times the symptoms come and go. IBD is comprised of two separate conditions of the GI tract, Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative Colitis (UC). Both of these conditions cause extensive inflammation of the GI tract but also can often be distinguished by different manifestations.

Newsletter

Most Popular

- 07 May 15

- 02 Sep 15

- 09 Jul 15

- 13 Apr 15

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 17 Jun 13

- 01 Jul 13